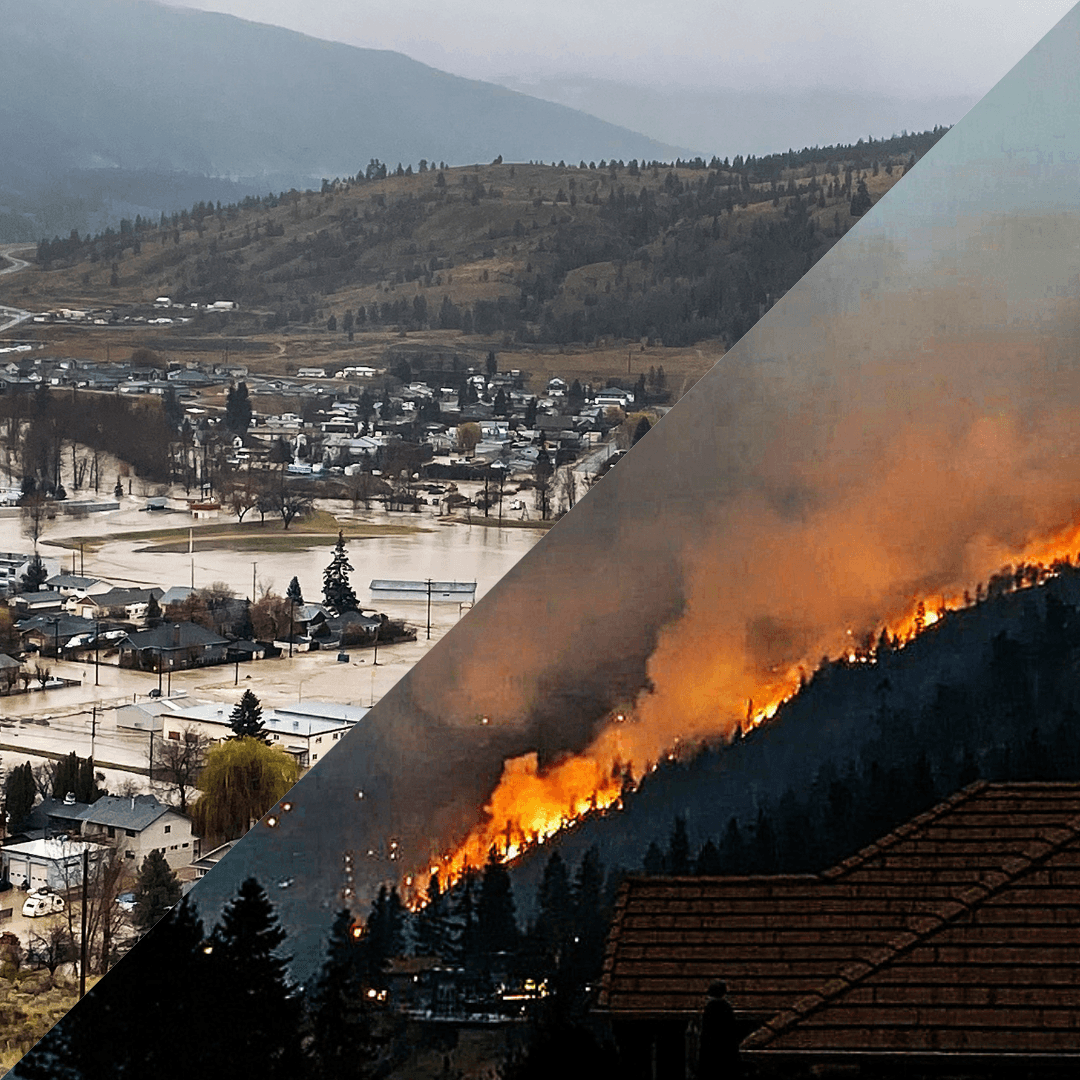

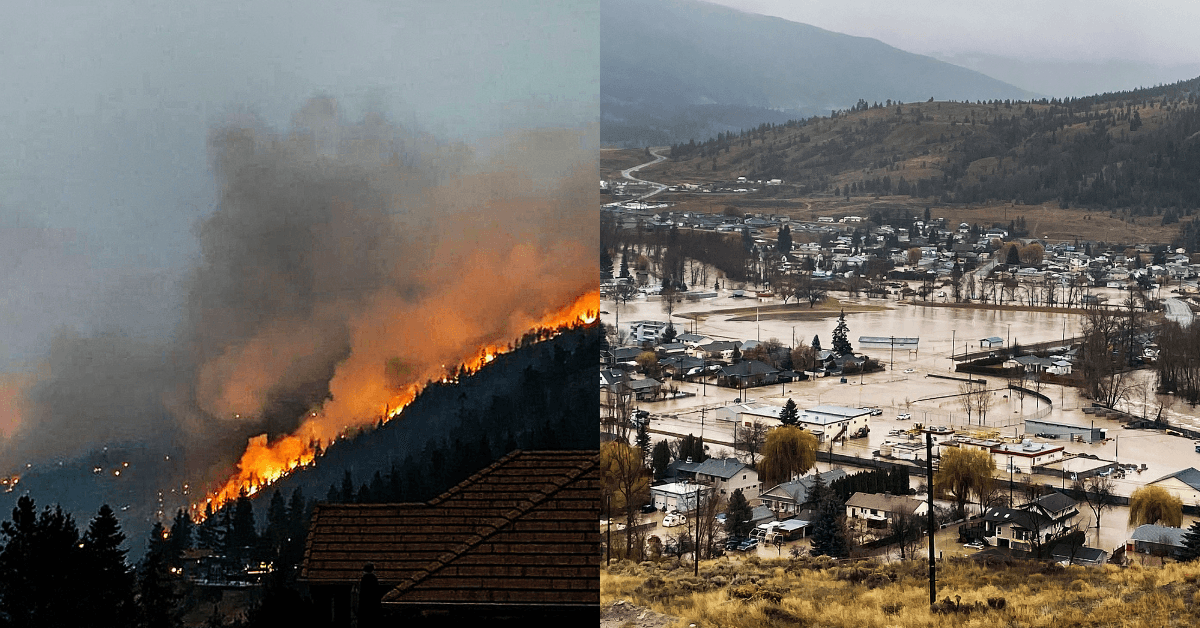

As evidenced by this year’s wildfires, no area of Canada is immune from the ravages of drought. Areas of all 13 provinces and territories were charred in 2023, with Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia and the NWT experiencing major fires beginning as early as March. But late into the fall, as is almost always the case, wildfires in BC became the country’s most deadliest and dangerous. Of the record 185,000 square kilometres of Canada that burned this year, some 25,000 square kilometres were in BC.

Of course, the potential for disaster doesn’t end with autumn, nor is it limited to wildfire. BC is increasingly enduring catastrophic atmospheric rivers and flooding. The threat became abundantly clear in November of 2021, when a series of atmospheric rivers resulted in destroyed homes and sections of important infrastructure including the Coquihalla Highway—something that no one thought possible up until then.

The reason for these weather extremes? According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the underlying mechanism for our province’s vulnerability is a rapidly-warming Pacific Ocean—particularly the waters of the western Pacific.

On its website, NOAA explains that the Pacific Ocean is like a swimming pool with its heater turned on—the areas of water closest to the heater increase faster. “If one thinks of the Pacific as a very large pool, the western Pacific’s temperatures have risen over the past few decades as compared to the eastern Pacific, creating a strong temperature gradient, or pressure differences that drive wind, across the entire ocean in winter,” the agency says. “In a process known as convection, the gradient causes more warm air, heated by the ocean surface, to rise over the western Pacific, and decreases convection over the central and eastern Pacific. As prevailing winds move the hot air east, the northern shifts of the jet stream trap the air and move it toward land, where it sinks, resulting in heat waves.”

Meanwhile, in the cooler months, this overall warming trend creates opportunities for more powerful and drenching storms of the type that washed out portions of the Coquihalla in 2021. To a large extent, it’s all about thermodynamics and how much moisture can remain aloft in the atmosphere. In the 19th century, two researchers, Germany’s Rudulf Clausius and France’s Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron, proved that, for every one degree Celsius of temperature rise, the amount of water that can be held by the atmosphere increases by seven percent.

In Canada, from 1948 to 2022, it’s estimated that the average temperature has increased 1.9°C. So these days, any system moving into BC off the Pacific coast could be carrying almost 15 percent more rain than it did 75 years ago, and the situation will continue to worsen as global warming continues.

In practical terms, all of this means one thing: as a citizen of BC, your chances of having to evacuate your home are escalating.

Data showing just how many people are evacuated each year in BC, and for how long, is not readily available. Earlier this year, frustrated by this fact, the respected independent news website The Tyee worked with Vancouver data scientist Jens von Bergmann to get a handle on this by examining data and census information from the past six years.

“People in BC are being evacuated, on average, for approximately 22 days, according to figures over the last six years,” wrote The Tyee reporter Francesca Fionda in April 2023 in an analysis of the findings. “Since 2017, there have been over 1,400 evacuation orders across the province and about 97 percent of those lasted over three days. Over that time, the BC government told us they spent over $49 million to support approximately 113,453 evacuees through the Emergency Support Service program. The last fiscal year cost almost half of that funding at $23 million.”

Note that these figures don’t include the estimated 35,000 British Columbians who were under evacuation order at some point in 2023 due to wildfires.

Fire and flooding are indiscriminate. Nobody gets a free pass from evacuation— and that certainly includes SCI BC peers or anyone who uses a wheelchair. We reached out to a trio of our peers who have been recently forced to evacuate, and they were willing to share their stories with the goals of giving readers some insight into their experiences, and providing them with information as they ponder the increasing probability of needing to evacuate as the climate situation worsens.

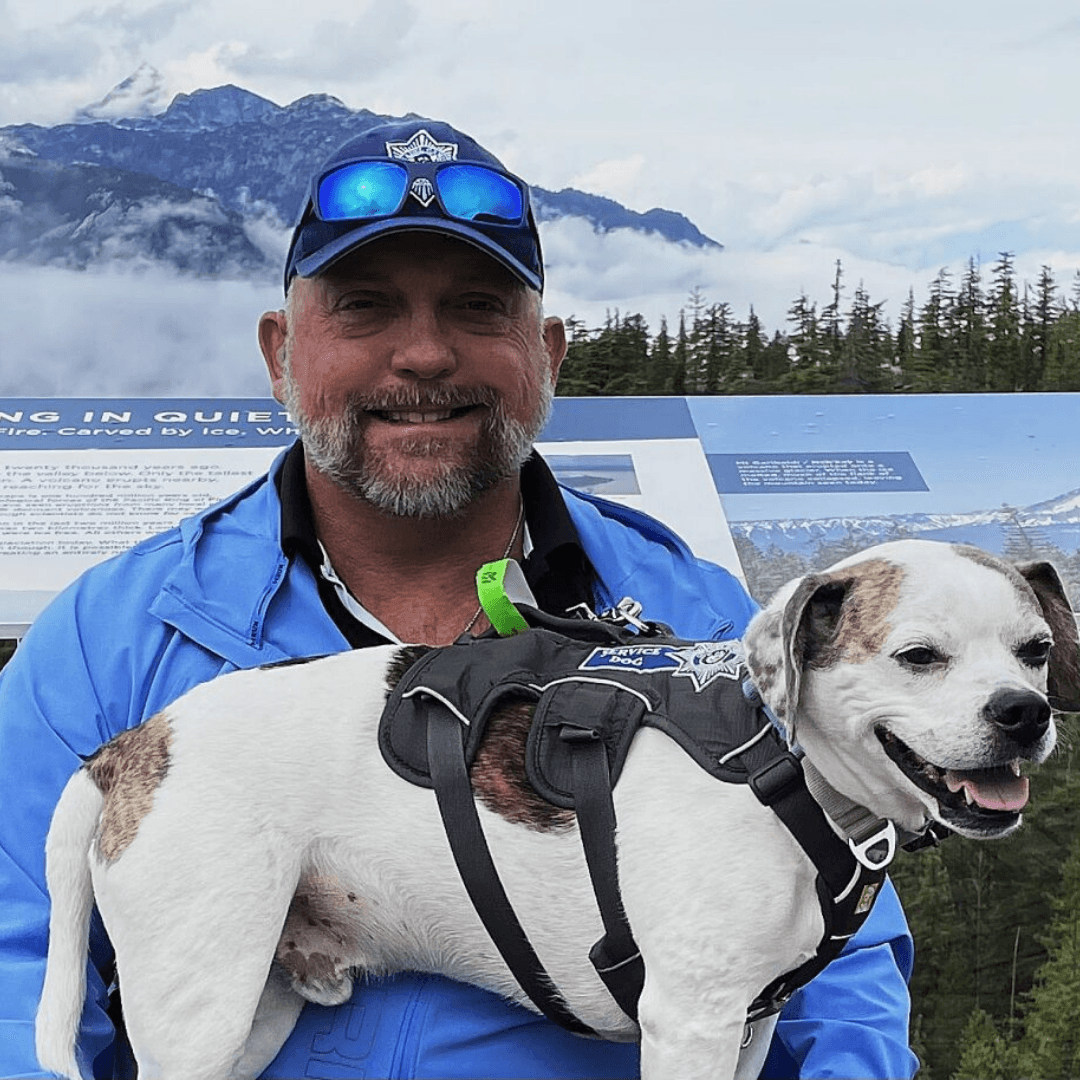

Rob Pullen

You might assume that anyone with military experience might be better prepared for an evacuation than most, and that’s certainly the case with Kelowna’s Rob Pullen.

During the 80s and 90s, Pullen spent eight years in the Canadian Army, serving a tour in Bosnia with our country’s peacekeeping forces deployed in the Balkans. An SCI resulting in paraplegia ended his combat career, but Pullen has never stopped leaning on his training throughout his post-military life.

Today, Pullen is retired, making his home with his husband Warren and their two dogs in Kelowna’s Wilden community. Life is usually peaceful for Pullen, who enjoys wheelchair curling, weight training, camping, sit-skiing, and just being outside. But on August 17th, things got a little hairy.

“We came home around 5 PM and noticed the large fire in Westbank,” says Pullen. “By 6 PM, I felt that the fire would jump the lake, so I started packing essentials into our two SUVs.”

Those essentials included medications, medical equipment, tools, emergency food supplies, legal documents, computers, medications, and Pullen’s immediate equipment requirements.

Pullen’s intuition paid off later that night. “We had finished eating dinner and I was planning to shower before bed in the event we were evacuated,” he says. “That’s when our neighbour banged on our door, telling us his friend’s house up the street just caught fire. We had zero time—as we were leaving the embers were flying down our street. There was never an order to evacuate, but we headed out and settled down close to city centre to figure out what we were going to do.”

As a veteran, Pullen got word that the Legion was available for anyone needing short term refuge, and that’s where they stayed that night. The next day, the couple decided to buy a new teardrop travel trailer for accommodation— it was a purchase they’d been planning for a while, as they wanted to join other SCI BC peers for some camping events.

“My concern as a person with SCI was comfort and security,” explains Pullen. “I needed space to stretch out, and a location to shower and use the bathroom.”

The Pullens initially set up camp at Prospera Centre’s parking lot, where they had access to food, water, and accessible toilets. A day later, they found a better alternative.

“We eventually moved to Orchard Park Mall as I had a gym membership there and knew other businesses that would open up for showers and toilets,” says Pullen. “We were also given the use of electricity by the mall manager. If we needed supplies, we went into the mall and spent our money there.”

A week later, they were able to move back home.” Our house survived, but the forest around us was hit pretty bad,” he says. “Our homes were built after the 2003 Kelowna fires, so they were built to withstand direct fires. If our home didn’t survive, we had friends and family who offered places to stay.”

Looking back, Pullen believes he was well-prepared despite the suddenness of the evacuation.

“As a military veteran, I have been trained to be ready 24/7 and taught that everything but life can be replaced,” he says. “As for my head space at the time, I have military combat experience, and in short this was nothing worse. I was more concerned for other people with disabilities.”

He concedes that, in hindsight, he and his husband could have done a few things better. “We should have bought the trailer prior to needing it for the evacuation. I also found that I was not completely prepared for one week, although my food and shelter was good. Medications and like supplies were where I failed by not having enough. I suggest a month supply for backup would be a good start.”

He has some other great advice for SCI BC peers who might need to evacuate in the future due to emergency.

“Ensure that you have all absolutely necessary equipment and supplies that would be next to impossible to get in 24 hours,” he says. “Ensure that you’re prepared and have gone over your plans both verbally, and actually do a test run each year. I strongly suggest doing one or more practice evacuations each year with helpers and without—this way, if you find yourself alone, it would be no different. My advice would be plan well ahead as if you were going camping, keep those supplies needed for camping close by for your evacuation. I would also make a local list of wheelers who have space or may need space to stay during event. And everyone should carry no less than $200 in small denomination bills.”

More than anything, Pullen stresses that people need to be prepared to rely on themselves, both in preparation for an evacuation, and during one.

“Everyone needs to understand that, no matter their level of ability, they all need to have plans, and only focus on the minutes or hours in front of them. Have a few options for evacuation plans and multiple people they can utilize for their safety. Only depend on yourselves and a few people who can help you if needed. Many I found leaned on their living facility for guidance, but this is where everything usually fails. Do not lean on any government agency for assistance, as I found many barriers with accessing assistance.”

Ryan Yeadon

For the two other peers we spoke to for this story, evacuation was forced by fire. But for 47-year-old paraplegic Ryan Yeadon, evacuation was the result of catastrophic flooding.

Yeadon was born and grew up in Merritt, BC. He moved to Alberta in the early 2000s. After recovering from a mountain biking accident in 2004, he enjoyed a successful career working with the City of Calgary, before moving on to the airline industry in 2010. Unfortunately, in 2020, Yeadon lost his job and his home due to the pandemic, and a seven-year relationship was also a casualty.

He decided to move back to Merritt, seeking a fresh start and a reconnection with old friends and family.

Everything changed in November 2021, when Merritt and several other BC communities were struck with a catastrophic triple atmospheric river event. In the early morning of November 15, the Coldwater River swelled to a level two and a half times greater than any engineering studies had predicted, easily breaching its muddy banks and overcoming dikes that had been prepared. Within hours, much of the town was under water. All 7,000 residents of the town were forced to evacuate, including Yeadon, whose house was positioned just a hundred metres from the river that carved six foot deep channels through yards, shifting houses off foundations.

“The police knocked on the door around 4:30 AM that morning,” recalls Yeadon. “We spent some time gathering any important documents, securing my pet, and locating medical supplies I would need for life during and after the evacuation. Within 20 minutes, it was already too late to safely leave the home in my chair, and it then basically just turned into getting as many possessions up off the floor and out of the crawlspace while we waited for the fire department to bring in their boat to get my senior mother and myself out of the house.”

They were rescued by the fire department at 6 AM, just as the entire first floor of the house became submerged, and taken by boat to a dry road where they were picked up by a friend.

The Yeadons, along with other members of their community, were given surprisingly little time to prepare for the flood—in fact, British Columbia’s River Forecast Centre (RFC) only issued its first warning at 5:30 PM on November 14. Despite that, Yeadon says he was prepared.

“I can’t really say there is anything I would have done differently,” he says. “Working for the airlines, I did a lot of travelling, so I pretty much just prepared like I was taking a normal trip away from home. I left with my wheelchair, an extra pair of pants and underwear, my commode chair, baby wipes, catheters and gel, my cat, and some food and a litter box for him. The biggest issue that I dealt with was simple basic needs like using a toilet. My number one concern that morning was making sure my commode chair was brought with me—there was zero chance I was gonna put myself in a position where I had to rely on Red Cross (or whoever) to try and find acceptable medical equipment for me to keep my dignity.”

Strangely, Yeadon doesn’t remember being overly stressed that morning— something he credits his cat for. “For me,” he says, “having my pet with me helped me block out a lot of stuff—it really allowed me to just focus on what was right in front of me.”

Yeadon had no choice but to live in hotels during the following months. Over the next two years, the home was repaired and renovated, but by that time, Yeadon was long gone—before the flood, he’d already been having doubts about staying in Merritt.

“The night before the flood came through town I realized that Merritt was not a healthy place for me,” he says. “I went to bed trying to figure out what was gonna be my next step. Waking up to water completely surrounding the house—and eventually my bed—made it pretty simple to accept that that my life in Merritt was done.”

And so, after five and a half months of hotel life, Yeadon came to the heartbreaking realization that, for his own mental health, he could no longer stay there and returned to Alberta.

“My advice to anyone with an SCI is to always be ready to go,” says Yeadon, who now lives in Grande Prairie. “Have your supplies topped up, know where they are, and keep a mental note of what you use daily and what you can’t get through a single day without.”

William McCreight

Unlike the other two paraplegic peers who are sharing their evacuation stories, William McCreight’s perspective comes from the position of being an incomplete quadriplegic.

Originally from Merritt, McCreight lived in Kamloops for about ten years before moving to Kelowna with his girlfriend, Emily, this past August. The couple’s newly-purchased West Kelowna home wasn’t threatened by this year’s wildfires, but if it had been, McCreight would have relied on the hard-won experience he gained when he had to evacuate his Kamloops home two years earlier.

Ironically, McCreight had been packing his van to go camping for the July 2021 long weekend when the need to evacuate became paramount.

“I was at my house and I got a phone call from a friend,” says McCreight. “He said, ‘Hey, you better look out your window. There’s a big fire that’s burning between Valleyview and Juniper Ridge.’ I was like, ‘Okay, well I better roll outside and go have a look to see how this is.’ I went about 300 yards to the corner of the street. And that’s when I saw this massive fire that was working its way closer towards where I live.”

Emily was visiting McCreight at the time. The couple raced back to the house and started to add some belongings to what they’d already packed for their camping trip. McCreight says his entire focus was on making sure he had his medical supplies and mobility equipment. He estimates they had about 15 to 20 minutes to evacuate. But despite the urgency, he remembers staying calm.

“I wasn’t that worried, because I’ve lived and been around some forest fires when I was able-bodied,” he says. “My girlfriend, Emily, was definitely more stressed. She was born and raised in the GTA, so she had never experienced anything like this before—it was very scary for her to go through.”

The single road from McCreight’s community was bottle-necked with traffic, which caused some confusion and concern. But eventually, the pair made it to a safe location on the side of the Trans Canada Highway. They watched the fire for a few hours, all the while receiving invitations for shelter from friends and family. Ultimately, they made their way to a fellow peer’s accessible home, located in a safe part of Kamloops.

A few hours later, the grass fire had been largely contained, and they got notice that the house was safe and they could return home. The next day, they packed up the rest of their stuff, and left to go camping.

Looking back, McCreight says that, for the most part, he’s happy with how the evacuation went. But he concedes that it might have gone worse had he not been in the process of packing for a camping trip. And he recognizes that a power failure would have complicated things—for example, he’d been by himself, he wouldn’t have been able to manually open his garage door to get his van out. And he also says he was fortunate Emily was with him at the time.

“It’s sometimes more difficult being in a chair. Just the fact that I can’t quickly grab a whole bunch of items in my arms and sprint down the stairs and throw it in the vehicle and go. I can’t just jump in the vehicle in five seconds and be out the driveway. It takes me time to transfer. There’s all this stuff to keep in mind. For this example, it was fine, because I had Emily there to help me grab things. If it was just me, it would have been difficult to grab those items in that time. I would have had to decide how much time I needed to safely get as much as I could get, and I would have just had to hit the road.”

There are other things he says he could have done better. “It wasn’t until I left my house that I realized, wow, I left a lot of things behind that I wanted to go back for—I didn’t even really put two and two together to grab stuff like my passport and personal belongings,” he says. “When I got home and I saw all these things in my house, I wish that I had made a list when I was of sound mind.” He recommends peers create a list like this.

“Put everything on there that’s very important to you,” he says. “Then at least you have your list at all times, somewhere safe, ready to go. And when you know it’s getting bad or fires are kind of starting to get close, where you may have to be evacuated, that’s when I would pack up and have things ready at the door. So if you get a knock on the door, get your list, get your go-bag, and you’re on your way.”

Another thing he’ll do in the future is grab all of his medications, and not just a week’s supply.

“If you had to leave or go to a different town, it can just be a pain to try to get prescriptions filled and have to deal with that,” he explains. He also would try to bring more items of sentimental value, although he concedes that they would take a back seat to essential items if the situation was really urgent.

“Actually, in summer, peak season, possibly pack a bag, so it’s faster to grab on your way out the door,” he recommends. “I think my go bag would basically just be three months of medical supplies, or something like that. Just bring three months of all of my medical supplies and have it convenient and ready to go. And then have that list of stuff to grab. And have that in a convenient spot. So when you’re in a panic mode and you’re told you’ve got to leave now, you have that list and you can quickly grab a couple of things.”

He offers this final piece of advice to peers. “If it’s fire season or there’s a fire slowly getting close to where you live, always make sure you have a full tank of gas. The last thing you want to do is be in a big panic and rush to leave town and need gas—especially if you can’t get out and you’re gonna need someone to help you (pump gas) in a big panic and rush. That could be another scary challenge if the fire is getting closer to wherever you are and you’re scared and need to get away; it’s just gonna add extra stress and anxiety that you don’t need put on you.”

Be Prepared

There are many excellent resources available online to help you prepare for an emergency evacuation. Excellent starting points include:

This article was originally published in the Winter 2023 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Male infertility

- Adaptive gaming

- Exercise app for ambulatory peers

And more!

Read the full Winter 2023 Issue of The Spin online!