Giant’s Head Mountain is an Okanagan, BC landmark. Located in Summerland, this former ancient volcano has been shaped by centuries of glacial activity to now reach over 200 metres elevation and offer panoramic views of the surrounding Okanagan region. When making a summer visit to the mountain you might be taken aback not only by the beautiful scenery, but the surprising sound of skateboard wheels grinding on asphalt.

The Giant’s Head Freeride is an annual downhill longboarding event that brings together athletes and enthusiasts from across BC and beyond to compete in downhill races on the 2.1 kilometre vehicle access road winding around Giant’s Head. Amongst the crowd gathered for this past summer’s event was SCI BC peer Emerson Corduff.

For the unfamiliar, a longboard is a type of skateboard with a longer deck designed for stability and used for cruising, downhill racing, and freeriding. “Nothing gives you the same feeling as going down a hill on your skateboard and feeling the G-force and the wind go past your shoulders as you tuck down the hill,” Corduff says when describing his love of skateboarding. Corduff, who grew up in Vernon, BC, started skating after saving up enough money to buy a longboard for his 14th birthday.

“My buddy and I would take it down hills and try to figure things out for ourselves, but it’s not easy… there was a poster up at one of the skate shops for a ‘Learn to Stop’ session. I showed up one day and happened to be the only kid there. It was awesome. It was just a group of guys spending their free time teaching kids how to skateboard. They probably spent 40 or 50 evenings with me going over how to slide, how to corner properly, how to grab your board in the right place,” reflects Corduff on those early days.

With practice, Corduff started to improve and began competing in races throughout BC, the Pacific Northwest, and the SMR (San Marcos Road) freeride in California. His skills and his skating community continued to grow as he pursued his passion for longboarding into adulthood. “Everyone is just stoked on people learning things and getting involved in the sport. Even if you’re new, they want to talk to you and hear about your ideas and input,” he says. “You’re probably going to mess up and fall a lot, but if you’re not falling, you’re not learning.”

Corduff knows the meaning behind this mindset all too well. In 2023, he was involved in a vehicle roll over accident while working at a local ski hill that resulted in a T9 SCI. Shortly after the accident, he was transported to G.F. Strong where he began rehab and the difficult journey of learning about life with an SCI. When asked about this period of time, Corduff unexpectedly smiles. “My skate community was there from the first day I was injured,” he says. “A lot of people are from Vancouver so they were there right away and overwhelmingly supportive… Calgary is also a big hub for skaters and I had a lot of friends drive over to visit for the night and then drive back the next day for work. People were bending over backwards to help us. They’re friends, but they’re really more like family in the way [we] help each other.”

Nigel Corduff, Emerson’s dad, was the first person to learn about his son’s injury and remembers how the skate community jumped into action. “Nobody wants to get that phone call. I was driving to Vancouver and [still] had five and a half hours to get to where Emerson was… When I found out he was awake at Vancouver General and alone I picked up the phone and called one of the skateboarders and told him the news. He was really choked up, but just asked, ‘What do you need from me?’ And he was there right away, in typical skateboard fashion,” he explains. “When I got there, the longboarders had saved a parking spot for me and gave me a hot cup of tea. They showed me where to go and I went into Emerson’s room and—I couldn’t believe—[he was] smiling! Someone had snuck in a kitten who was walking all over Emerson and tickling his face. It was a world of ICUs and elevators, compromises and money, and a lot of stress. But we got through it and the skateboarders were there all the time.”

During his stay at G.F. Strong, Corduff met Ryan Clarkson and Marta Pawlik, SCI BC Peer Program Coordinators, who introduced him to SCI BC. Similarities between the skate community and the SCI community were immediately apparent. “The willingness for people to talk about anything and to be able to connect with everybody is awesome. Everybody’s included and it doesn’t matter what your situation is, you can hang out and be yourself,” Corduff says. For the last two years, he’s attended the SCI BC Whistler Adrenaline Weekend to meet other peers and explore other adrenaline-fueled hobbies like mountain biking, rock climbing, and kayaking, but his passion remains with skateboarding.

Following his injury, Corduff wasn’t sure if he would return to skateboarding, and if he did, what would it look like? Local Kimberly, BC skater, community mentor, and Berley Skate skateboard manufacturer, Jody Willcock, heard about Corduff’s injury and began working on a solution. “Twenty years ago I was approached by a competitive sit skier to help build a summer cross training device [that would] mimic ski racing on a skateboard,” he explains. “I stored the molds because of their odd nature and the time put into them… after Emerson’s accident, [we] pulled the old molds out again for another pressing.”

This time, Willcock updated the prototype with triaxial glass, a strong flexible fibreglass often used to make skis, and incorporated Hollowtech, a production method that reduces weight by using composite materials instead of traditional wood. The result was a lighter, more agile, and more versatile design. “I didn’t talk to anyone about it, not his dad, no one. I wanted it to be Emerson’s choice whether he rode this or not.”

In 2024, less than a year after his SCI, Corduff and his dad decided to go to Kimberley to visit Willcock and attend the Sullivan Challenge—the longest running downhill skateboard race in the world. “I was really worried,” Corduff’s dad recalls. “[Emerson] used to compete in this event and now he was going to be on the sidelines. This was kind of a make or break for his recovery as a person.”

After a seven hour drive, they arrived at Berley Skate and were greeted by the skate crew. “We were going there just to watch the event and I wasn’t going to be racing. But as soon as we rolled around to the factory everybody was there and they had this big pressed out board. Before my dad could even park the car, I was on it getting pushed down the alley,” Corduff says. “I had been thinking about getting back into adaptive skating, but I hadn’t talked to anyone about it. Then we showed up and they surprised me with this. It was wonderful.”

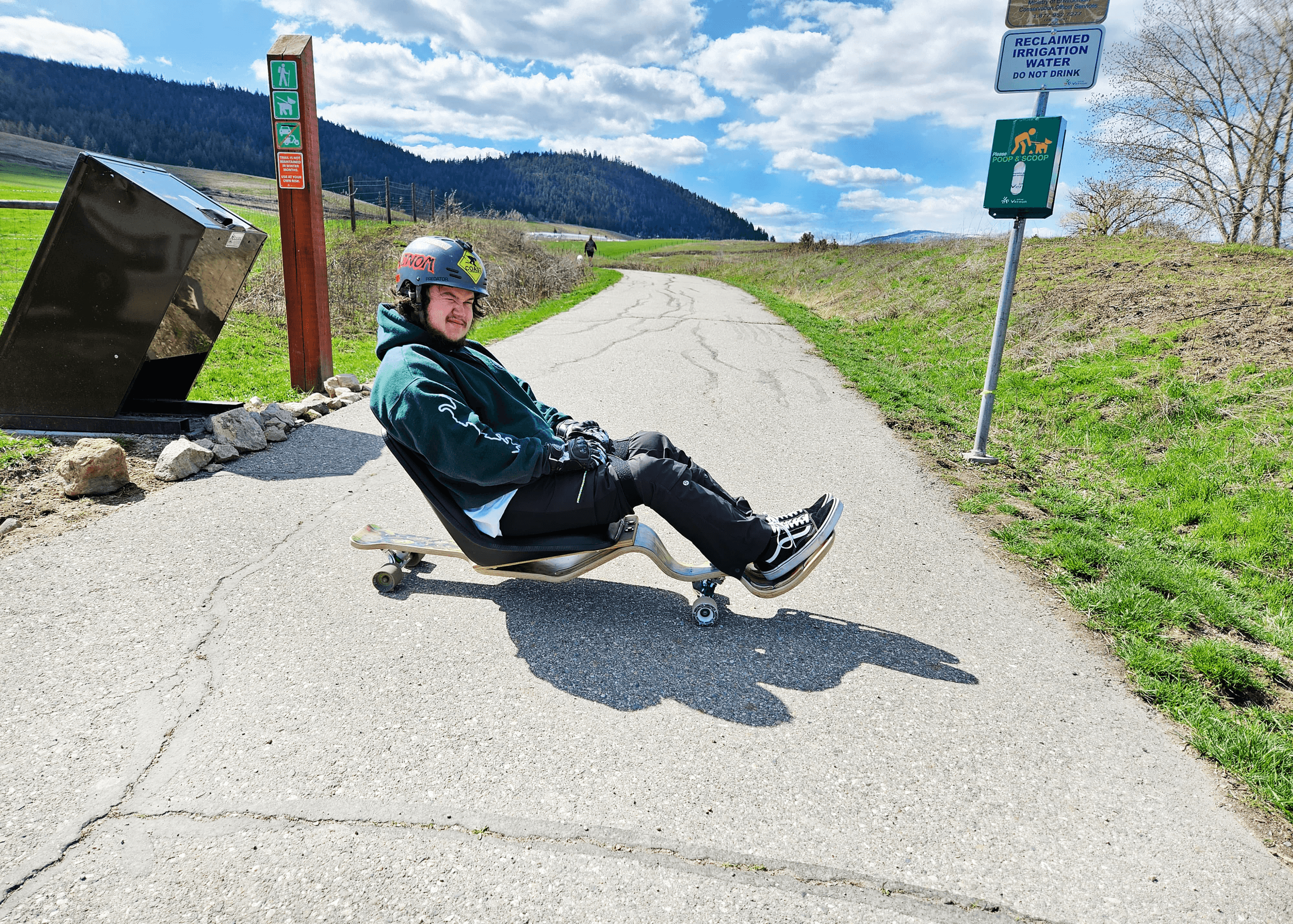

A year later, Corduff and Willcock discussed how adaptive skateboards could benefit so many more people and they began refining their initial prototype. They landed on two main models: The Lounge longboard and a racing longboard. The Lounge model is for leisure riding and is designed to carve corners smoothly using the weight and momentum of the rider’s body. A seat, similar to a sit ski bucket, is affixed to the top of the board which allows users to socialize with friends in an upright position while they ride. “I want to make it as affordable for the community as possible, “Corduff says. “It shouldn’t be for just a select group of people. I want it to be for everybody. You should be able to just cruise around outside or go down the road if you want to, not in your wheelchair.”

The Lounge is currently available for pre-order as a standardized board deck that can be customized to meet your personalized needs or wants. Additions like foot pans, custom board length, or e-propulsion methods are all considerations. It can be used by people with SCI as well as anyone who may have balance or coordination limitations, mobility issues, or just want to try something different.

The racing longboard model is still in development, but features a more stream line design, side panels and leg straps for safety, a shorter board for speed, and a disc brake system connected to hand controls. “I’ve ridden on the [current racing prototype] on a couple of my local hills, on the Maryhill course down in Washington, and on Knox Mountain in Kelowna,” Corduff says. “It felt pretty crazy going downhill again. My first time luging after my accident was at Maryhill, which I had actually never even skated before. I was riding down the hill and at some point just thought, ‘Ok wow, we’re actually here now’… It was awesome to get the adrenaline pumping and have that feeling again.”

At present, Corduff races alongside able-bodied riders, but he hopes adaptive racing will gain more popularity and recognition.

“There’s something called the Stoke,” Corduff’s dad says. “It exists in the longboard community and it’s not a fake thing at all. This tragedy has happened but life goes on and the Stoke continues… [it’s] an environment where Emerson can excel and grow into whatever kind of future he wants.” For Corduff, this future is already taking shape. He’s committed to improving adaptive longboard designs and sharing them with as many riders as possible so the sport can grow. He also hopes to compete in the World Roller Games, the downhill skateboarding equivalent of the Olympics, when adaptive racing is recognized as its own event.

In the meantime, Corduff has his sights set on conquering Giant’s Head Mountain. “That one is a little daunting,” he admits. “Some of the falls aren’t great if you mess up.” Still, he knows better than most that falling is all part of learning.

You can connect with Corduff on Instagram at @thesk8erlounge or by email at sk8erlounge@gmail.com. The Lounge longboard is now available for pre-order! Learn more at thesk8lounge.com.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2025 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Mindfulness

- Ozempic

- Menopause

And more!