We asked a few SCI BC peers with incomplete SCI and ambulation to answer one question: if you had the opportunity to tell the public—and even your friends and family—about the nature and implications of your injury, what would you say?

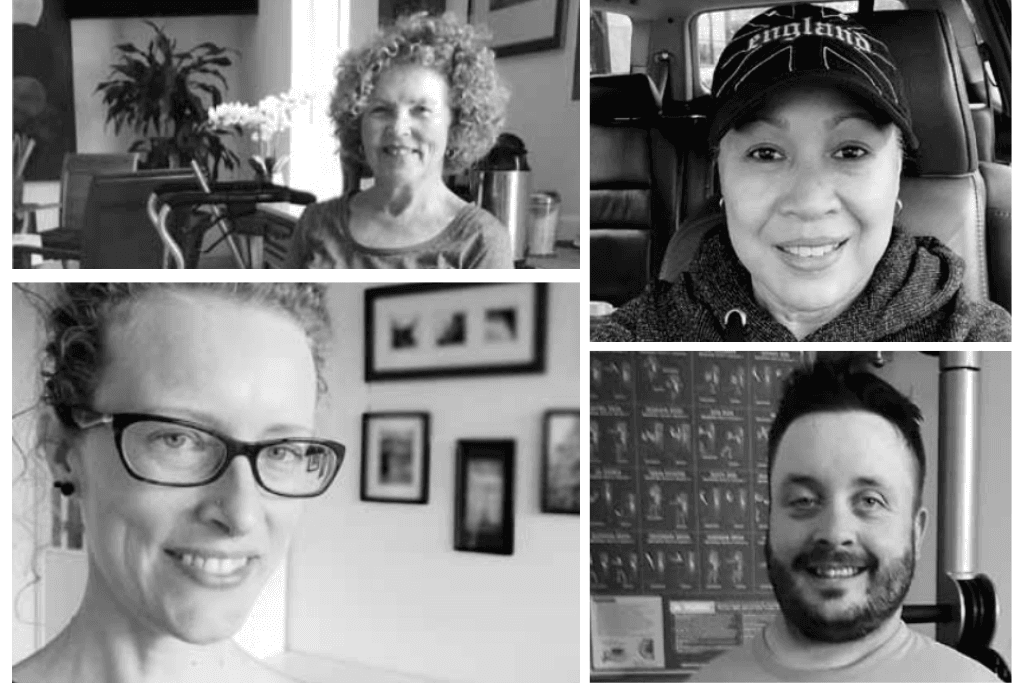

Our thanks to Gord Rant, Noreen Segui, Susan Cush and Lisa Hislop for sharing their insights about their post-injury lives.

GORD RANT | VICTORIA, BC | C5 INCOMPLETE, 25 YEARS POST-INJURY

If I could have my family, friends, and members of the public know just one thing about my disabilities it would be that they don’t define me. They’ve given me the opportunity to grow and persevere through many challenging situations, and have taught me many valuable life lessons that I may not have learned had I not had them.

That being said, I have an incomplete injury and can walk a little bit, and a lot of times that gives members of the public the impression that I don’t need my wheelchair or other sorts of mobility aids—which is untrue and frustrating a lot of the time.

When I go to sit in my wheelchair after going for a walk, or stand up from my chair to stretch, a lot of people give me some dirty looks. I think people just need to take a little more time to understand that disabilities are all different and present themselves in different ways

NOREEN SEGUI | VANCOUVER, BC | C2-C5 INCOMPLETE, FOUR YEARS POST-INJURY

I had a very difficult recovery. I have chronic pain, am very slow when I walk, and can’t walk far. I still have hypersensitivity that also won’t go away. The most common questions I get from people that I meet who don’t know me is, “What’s wrong with your legs?” or “Did you hurt your legs?” I get tired of explaining to people that I actually have an incomplete SCI. I can explain what had happened, but I’m not really sure if they understand my situation. I want them to know that there is more to this than meets the eye—the chronic pain, hypersensitivity around the area of injury, fatigue, both legs feeling very heavy, etc.

When I became an SCI BC member, I learned to communicate my situation better because I talked to people who have the same experiences as I do. Walking or non-walking, we have common experiences that made me realize that I’m not the only one going through these problems.

SUSAN CUSH | VANCOUVER, BC | C2-C4 INCOMPLETE, 43 YEARS POST-INJURY

I tried so hard to be “non-disabled”. During my 30 years of working hard as a nurse, I didn’t talk about my injury. Instead, I pushed on through the pain of contractures in my feet and legs. I didn’t question that the painful lumbar spine at L4 L5 was anything other than a work-related injury. I didn’t clue in to the fact that the urgent surgery to fuse my neck in 2018 at C2 C3 C4 C5 was related to a common problem of spine fractures—breakdown at the fracture site. Nor did I realize that osteoarthritis in my left knee was anything more than an inherited familial flaw.

I should have realized that I didn’t have anything to prove physically. As life progresses, we increasingly become the “walking wounded”. We fall easily and are affected not only by frequent ongoing injuries but also by the non-visible problems of other quadriplegic people—neurogenic bladder and bowel, and autonomic dysreflexia. An incomplete SCI is life-changing; you might seem normal to others, but your life is not—and never will be—as it used to be or could have been.

Today, I use a walker and have for the past 10 years plus. I am very cognizant of accessibility with regard to stairs, scatter rugs, carpet, etc. After outpatient physio at GF Strong last year, the physiotherapist and OT both recommend that I move to get an electric wheelchair because of frequent falling. So far I’ve been pushing back on this as I am mobile and I don’t honestly have a wheelchair-friendly kitchen and bathroom. I’d be interested in hearing what other incomplete quads have to say about these things—the electric wheelchair option, frequent falls, and their solutions to common problems we face.

LISA HISLOP | VANCOUVER, BC | T12/L1 INCOMPLETE, 20 YEARS POST-SURGERY

The hardest part about having an incomplete SCI is that my adaptive needs are inconsistent. As someone who uses a wheelchair, but can walk with almost no impairment, I don’t fit the description of a disabled person, let alone a wheelchair user.

So, when I’m in a place where I’m doing both, and people don’t know me, I have to be careful. Something as simple as getting up from my wheelchair and going for a walk during a break can feel to others like a real betrayal of their trust. This seems like a bit of a dramatic claim, but some people have boldly accused me of faking to get attention—which I suppose is an understandable reaction, considering how few people I have seen rise from a wheelchair and walk. At the same time, I don’t want to have to delve into my personal history to satisfy their need for an explanation, or pretend that my injury is more severe than it is to avoid confrontation.

If I could share one piece of advice with the public, it would be to consider the person getting up from their chair (or sitting down in one) as being completely honest with you, rather than completely fake. No explanation needed.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Cannabis & Blood Pressure

- The High Cost of Prescription Medication

- SCI BC Peer and Musician

And more!