When most people think about virtual reality, or VR, they think about video games. They imagine someone with machine-like goggles strapped to the front of their face, making sudden and strange movements as they respond to what’s happening in the virtual world in front of them. From enjoying a round of golf to playing the guitar, or perhaps engaging in an epic quest to find hidden treasure while outsmarting enemy treasure-hunters along the way, we think about VR as a form of entertainment. What we don’t often think about, and what researchers around the world have been investigating, is how VR might be an effective way of alleviating neuropathic pain.

As a common experience for people with SCI, we know neuropathic pain—and effective ways of treating it—are top of mind for our readers. And while we can’t always promise concrete solutions, we do our best to bring you the latest developments in pain management research. For example, in the Spring 2013 issue of The Spin, we reported on how a group of researchers in England had stumbled on a way to reduce arthritis pain through video illusions (“The Power of Illusion”). This research, and a mounting body of evidence collected over the past decade, suggests that the key to relieving neuropathic pain resides in the brain, and that by correcting the brain’s ability to interpret and respond to incoming signals from the rest of the body, we have an opportunity to reduce (or possibly eliminate) chronic pain associated with SCI.

One way that researchers are testing this hypothesis is using VR to “trick” people into believing that they’re using or feeling their legs. And while we’ve reported on this research in the past (see “Great Pains” in the Fall 2021 issue of The Spin), a number of questions remain unanswered. More specifically, studies demonstrating the pain-relieving effects of VR for people with SCI have been conducted with small sample sizes, making the results inconclusive. And perhaps most notably, we still don’t understand how VR interventions are causing or contributing to neuropathic pain relief. So, when we found out about a large-scale clinical trial that’s testing how a virtual walking simulation game—called VRWalk—can reduce neuropathic pain among people with SCI, we were keen to learn more about it.

The VRWalk trial is an international collaboration between Immersive Experience Laboratories (a company that specializes in VR applications for clinical research), Virginia Commonwealth University, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and the University of New South Wales. According to the study’s primary investigator, Dr. Zina Trost, a clinical psychologist and health psychology researcher at Texas A&M University, the trial operates out of three sites at each partner university. Trost supervises the site at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she worked when the trial was funded.

VRWalk is based on mirror therapy, a technique used to treat phantom limb pain—a condition in which people with amputations perceive pain or discomfort in the body part that is no longer there. “We think neuropathic pain happens following the same processes that underpin phantom limb pain,” explains Trost. “Specifically, your brain has a representation of your body, and even if you sustained an injury, like you lose an arm, your body still has representation of that arm. And it’s the disconnect between the brain and the missing arm—a process called deafferentation—that creates a pain state. The same thing is essentially happening in SCI. The brain has lost contact, partially or fully, with a functioning part of the body.”

Mirror therapy involves tricking the brain into thinking that the affected or missing limb is moving by using a mirror to create a reflection of the unaffected limb. For people with SCI, early research with this technique involved using a mirror to reflect the upper body on top of a projection of walking legs. “These people were looking at themselves walking toward themselves, and it actually helped. That was a pretty striking result,” says Trost.

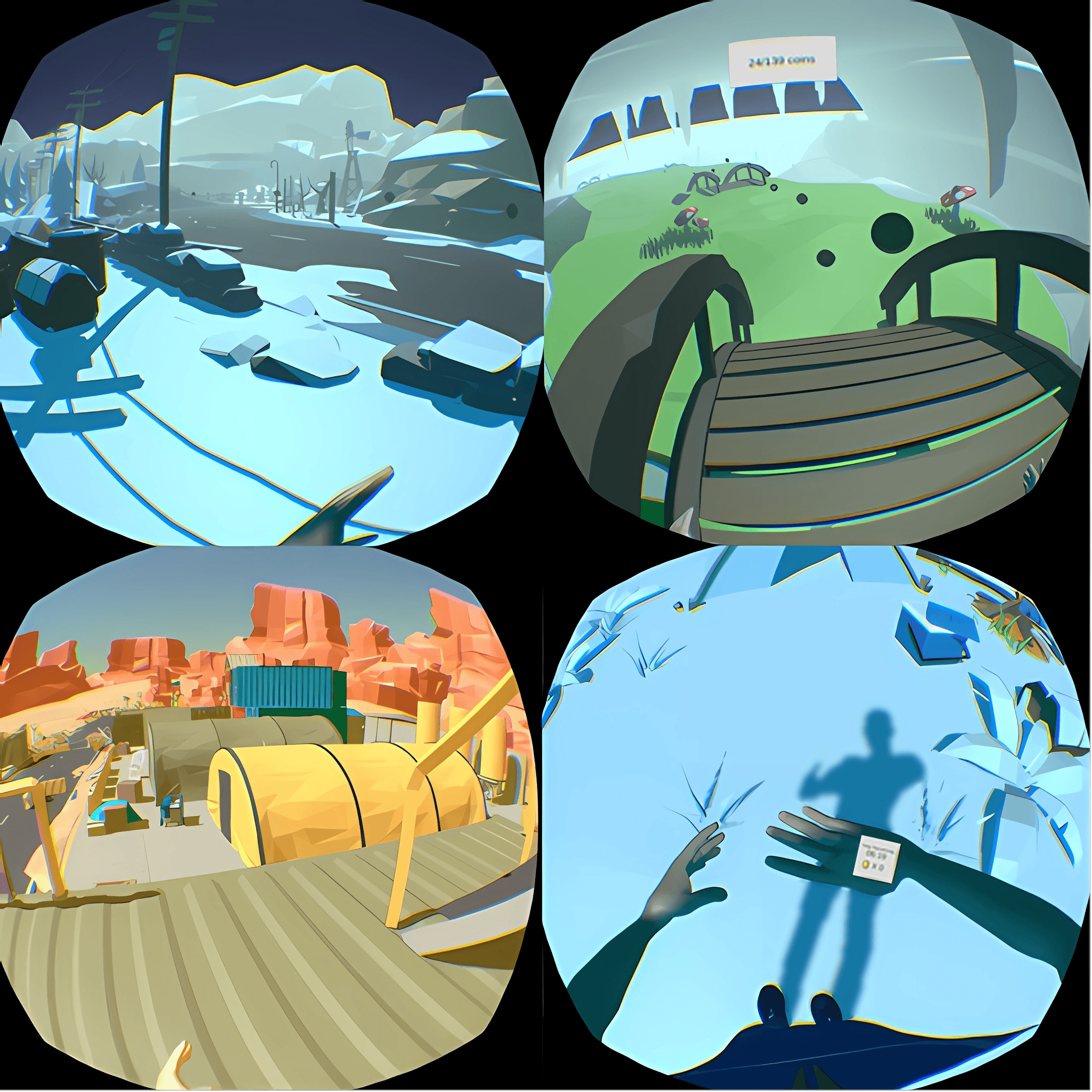

Building on research with mirror therapy, Trost and her co-investigators wanted to take the approach one step further using VR. Working with Immersive Experience Laboratories, the trial’s industry partner, and a group of stakeholders that included people with SCI, the team co-designed VR software that shows a first-person perspective of participants’ hands and legs while they walk through different environments, such as a snowy village or a desert outpost.

“One of the big things that really informed the product design was realizing that we, as able-bodied people, had a different experience testing the virtual walking intervention then people with SCI did. When we imagine ourselves walking, we restrain our muscles from actually trying to walk. Whereas it seems that people with complete SCI do not, so they had a much stronger experience of walking,” says Corey Shum, the Director of Immersive Experience Laboratories. “That was a discovery that really helped the whole process of product development and the study itself to know that there are neurological mechanisms there that we wouldn’t have guessed if we didn’t have people with SCI interacting with the product directly.”

In a preliminary study of 27 people with complete paraplegia, Trost and her team found that participants who used VRWalk over a two-week period at home reported not only significant reductions in pain intensity, but also improvements in mood. “The responses were positive and pain improvement was observed. This is the preliminary data that helped us get the bigger funding,” says Trost.

With funding from the United States Department of Defense, the VRWalk trial launched in 2020. The research team is aiming to recruit 188 people with SCI over a five-year period, and they are about one-third of the way towards that goal. According to Trost, the trial initially focused only on people with complete injuries, but earlier this year, the Department of Defense granted the research team with additional funding to include incomplete injuries in the trial as well.

The study involves playing the virtual walking game for 10 minutes, two times a day for 10 days. Participants also complete questionnaires before and after each virtual walking session, as well as 6 and 12 months later. The questionnaires assess self-rated pain and mood levels, as well as participants’ experience of the game. To examine the mechanisms underpinning changes in pain levels as a result of the virtual walking sessions, participants that live near one of the three project sites are invited to participate in an MRI to assess changes in the brain. While the trial is focused on virtual walking, it’s engaging lower body function more generally. “This is important because many folks [with SCI] don’t have neuropathic pain in their legs directly but around the site of injury,” says Trost.

A unique aspect of the trial is that the protocol can be completed remotely in participant’s homes without the physical presence of a researcher. Although this wasn’t the original plan, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that for the study to continue, the plan needed to change. So, the research team began mailing kits with all of the VR equipment required for the study to participants’ homes, and teaching participants how to use it over Zoom. With this approach, the team was able to increase the study’s geographical reach beyond the planned project sites.

“We built out a system that hadn’t existed before. And I was kind of expecting it to fall down around us, but it’s worked surprisingly well,” says Shum. “We ship it to them in a box. And then we give them a return label. When they’re done, they slap it on the box, and a study coordinator helps schedule a postal worker to come pick it up. Then we clean the units, sanitize them, reset them and send them back out.”

Participants are monitored remotely during the study to troubleshoot issues with the technology, and to make sure that the equipment is being used as intended. “We send a mobile hotspot out to everybody’s house. So, we’re in constant contact with their device,” explains Shum. “We can update it, and the [study] coordinators can view recordings of exactly what the participant experienced, along with other metrics, and we can make adjustments to their systems on the fly.”

Trost was initially concerned about the potential for people with SCI to experience negative psychological triggers while engaged in virtual walking. But none of the stakeholders with lived experience involved in the study design nor any of the trial participants have reported any negative experiences or concerns, says Trost. This could be due in part to the fact that the study only accepts participants who are at least one year post-injury, whose pain experience and medication regimen are more likely to have stabilized. “Although I do think that if we do this [intervention] early on, we can actually prevent development of neuropathic pain,” says Trost.

An issue that the research team has experienced with the VR technology is ‘simulation sickness.’ “With the technology, our main barrier to use is nausea. This happens in about 10% of the people that we encounter,” explains Trost. “So, we are trying, and experimenting, as we go with different ways to mitigate that nausea. You know, for example, creating different kinds of transitions from scene to scene.”

“I think, as technology improves, and as our software mediations improve, we’ll get better. But I don’t think it will entirely go away. Some people are simply more sensitive than others,” adds Shum.

Ensuring that the technology works well and can be adapted or custom-built for people with SCI has been both a challenge and a priority for the research team throughout the project. “We’re constantly working to improve the technology overall, especially in response to the information we’re getting out of all the stakeholders giving their qualitative assessment,” says Shum.

“We have a stakeholder team—groups of people who are not necessarily scientists who are included in our design team—that can help us shape the product,” explains Trost. In addition to the involvement of the stakeholder team, the study is co-led by Dr. Rachel Cowan, an Associate Professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham who has both relevant research expertise and lived experience with SCI. “In the virtual walking study, we had a lot of ideas that were corrected by people with lived experience, which was incredibly helpful, and this is why I think we’ve seen so much success with people being able to use it,” says Trost.

While the trial is ongoing, it has spurred additional lines of research centred on the virtual walking application. For example, building on research by VRWalk co-investigator Dr. Sylvia Gustin, Professor and Director of the NeuroRecovery Research Hub at Australia’s University of New South Wales, they will be extending their line of research focused on neuropathic pain by using VRWalk “to retrain people from both a top-down and a bottom-up approach to perceive touch,” says Trost. In addition to wearing the VR headset, participants in this study will place their feet on a device that provides touch-based stimulation while participating in the virtual walking game. The research team is also working on an exercise intervention using VRWalk. The goal of the intervention, says Trost, is to build an affordable, accessible means of exercise (at home) that would be tailormade for the SCI community.

Like the exercise intervention, what the research team hopes that the VRWalk trial will offer is an affordable, at-home therapy option that not only reduces chronic pain for people with SCI, but also provides an engaging experience. “What I would hope is that, basically, for people that have this kind of pain, we can just give them a little VR headset, right? That’s not very expensive, and they could have it like an asthma inhaler that they could use every once in a while,” says Trost.

According to Shum, the eventual goal is to have virtual walking software that could be used with any qualified VR hardware, whether it’s created by PlayStation, Apple, or any other company. “I can very easily imagine this being just an app that you download,” he says.

Findings of the VRWalk trial won’t be available until at least 2025, but here at SCI BC, we’ll keep track of new developments and keep you in the loop. In the meantime, you could get the inside scoop by trying the technology for yourself!

The research team is actively recruiting participants to take part in the VRWalk trial. Canadians with a complete or incomplete SCI who experience neuropathic pain are eligible to participate in the US-based trial, as long as the VR equipment can be shipped to their home address. To participate, you must be 18 years of age or older, use a wheelchair, and be able to use both arms at least a little bit. If you are interested in learning more, please call or text 1(804) 569-5965 or email sci@vrwalk.org. You can also visit sci.vrwalk.org/home.

Read more stories from the Fall 2023 issue of The Spin, including:

- A peer’s story of race car driving and family legacy

- Aging with SCI

- Accessibility in BC

And more!