Whether or not you’ve been following Simon Fraser University and ICORD researcher Dr. Victoria Claydon’s research on bowel care in The Spin for the last few years, if you live with SCI, you’re likely familiar with the challenges of bowel dysfunction. For example, in our Winter 2017 issue of The Spin, we covered a survey of 287 people with SCI led by Claydon. An undeniable 78% of respondents reported that bowel management was a problem, revealing just how many of you are dissatisfied with your bowel care routine.

“[The survey] told us that bowel care was a huge priority for people living with SCI. It wasn’t just an inconvenience or a frustration. It was a major priority, and it was having a major impact on quality of life and the ability to complete activities of daily living,” says Claydon.

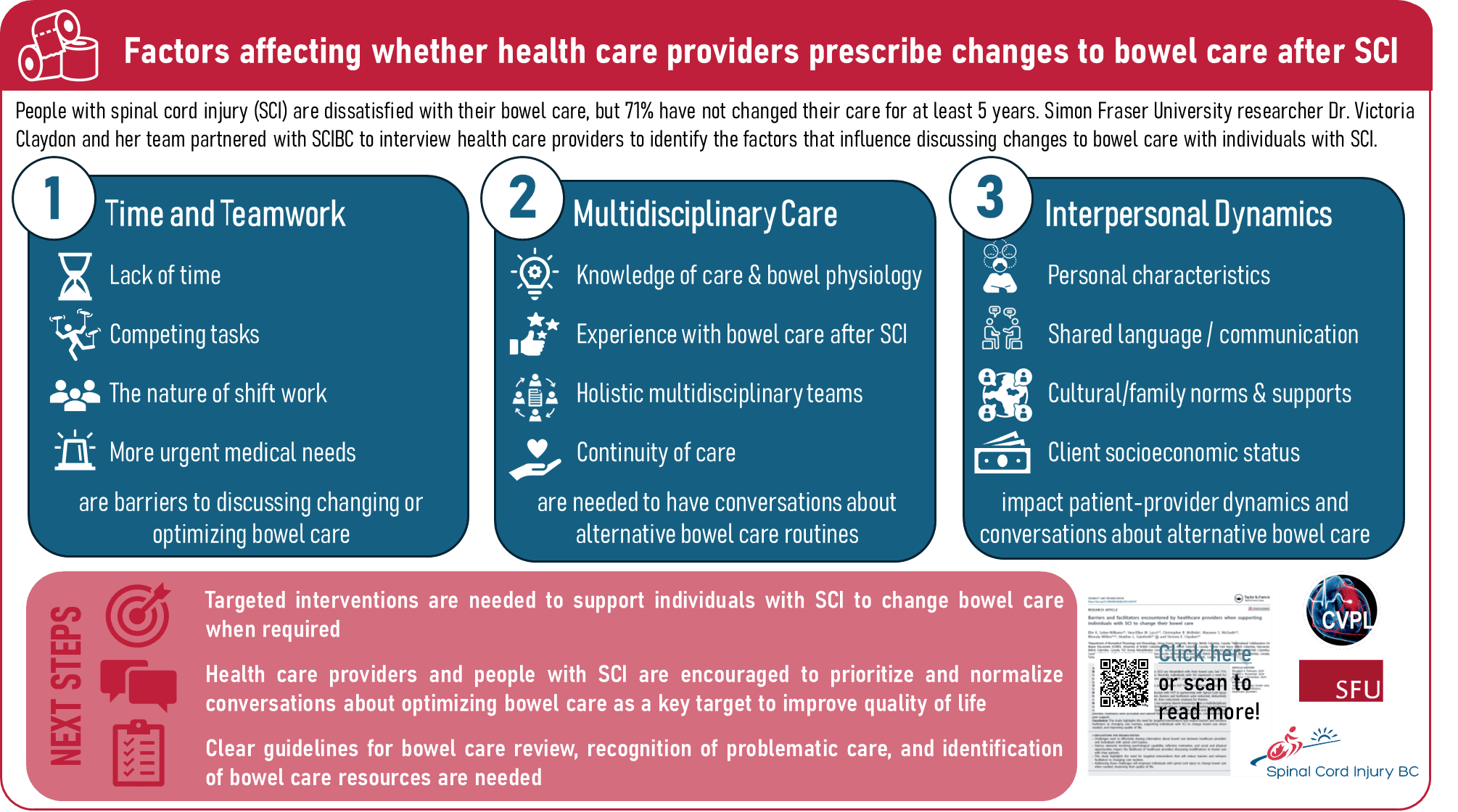

Respondents rated bowel management as one of the worst effects of living with SCI, citing how it’s a drain on time and resources, interferes with personal relationships, and triggers autonomic dysreflexia as some of the key issues. But despite these concerns, 71% of respondents had not made any changes to their bowel care routine in the last five years.

“Most people said they hadn’t changed a single aspect of their bowel care for more than five years,” says Claydon. “And we really wanted to dig into that piece and see why this poor quality care was not being addressed for people with SCI.”

These findings led Claydon and her research partners, including SCI BC, down two paths: First, they wanted to see if the voices they were hearing from people with SCI in the survey were reflected in the broader scientific literature. Second, they wanted to better understand why people with SCI weren’t changing their bowel care routines if they were so frustrated and dissatisfied with them.

Why Going Number 2 is Priority Number 1

To see if the voices they were hearing from people with SCI in the survey were reflected in the broader scientific literature, Claydon worked with SCI BC and a team of researchers to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis. Using this approach, they combined and analyzed the data from multiple published studies to draw conclusions based on the body of evidence as a whole.

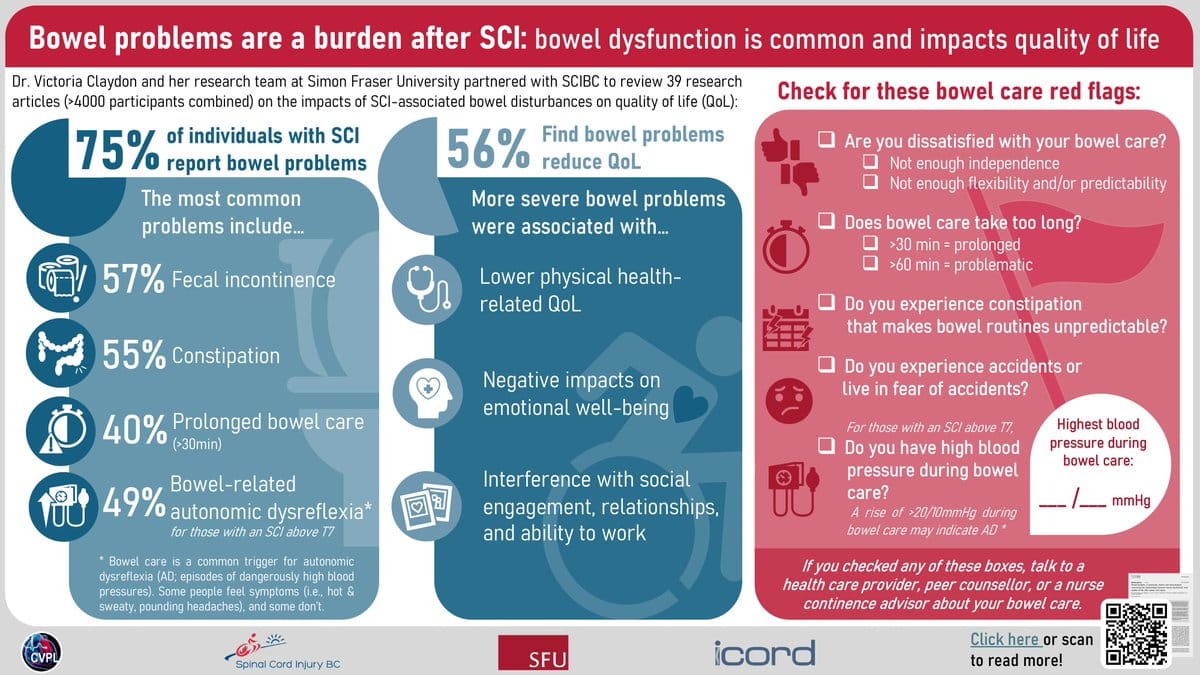

The study, published in the journal Spinal Cord in the spring of 2024, evaluated the extent of bowel dysfunction after SCI and the impact of bowel dysfunction on quality of life. After searching five databases, the authors identified 39 research studies representing 4,000 participants to review and analyze. The results not only validated the survey findings, but also highlighted important nuances concerning the impact of bowel dysfunction on quality of life.

“In the survey we had almost 300 people and nearly 80% of them said that bowel care was a major concern for them. In our review of the published scientific literature, when we combined responses from all the papers and all of the people who had participated in all of those papers, we had just over 4,000 people’s voices reflected. And the people who felt bowel care was a major problem is about 75%. So that’s a pretty strong parallel between the lived experience and what the data’s telling us,” says Claydon.

Across the literature, participants with SCI reported fecal incontinence, constipation, bowel-related autonomic dysreflexia, and prolonged bowel care routines as the most common problems with bowel dysfunction. As a result, more than half of participants (56%) reported moderate to severe deterioration in quality of life and nearly two-thirds (64%) reported that they fit their lives around their bowel management a little or a lot.

“We saw those key priorities that impact care and quality of life are the long time to complete care, problems with incontinence, problems with constipation, problems with autonomic dysreflexia…but it was teasing out the particular impacts on the domains of quality of life that was interesting in the systematic review,” explains Claydon. “Emotional wellbeing, social engagement, relationships, ability to work… those were the key domains.”

Qualitative research included in the systematic review showed that impacts on physical health (including a lack of predictability, secondary complications such as fissures or rectal bleeding, and pain or discomfort), emotional wellbeing (including feelings of frustration, irritability, and distress), and social life (including interference with relationships, lifestyle, and ability to work) are common and intricately connected consequences of bowel dysfunction.

“We decided to include any paper that addressed the subject, including qualitative research, meaning research involving interviews and surveys, as well as numerical data,” she explains. “I think it gave [the findings] new perspective that you can’t always capture in a number.”

For instance, the qualitative data showed how the fear of incontinence episodes could be just as debilitating as experiencing an episode itself. “You might not be having very frequent incontinence concerns, but if you have them at all and you’re worried that you might get one, it impacts quality of life and it plays a role in your ability to fully participate in, for example, social activities or a work environment,” says Claydon.

Change Takes a Village

Another question that Claydon has been working to answer is why people with SCI aren’t changing their bowel care routine if they’re so dissatisfied with it. Partnering with SCI BC and local SCI physicians and nurses, Claydon and a team of colleagues interviewed 13 people with SCI about the factors that make it easier and harder to change their bowel care routine. We covered the results of this study, which was published in the journal Spinal Cord in 2022, in the Spring 2022 edition of The Spin.

From the interviews, the research team identified seven factors that influenced changes in bowel care: Workplace flexibility, opportunities or circumstance, access to resources, beliefs about the consequences of change, perceived support, peer mentorship, and knowledge of available options.

- Workplace flexibility: When participants were engaged in a flexible and supportive work environment, they felt empowered to make changes.

- Opportunity or circumstance: Sometimes optimizing another care routine like bladder care gave people the opportunity to now focus on their bowel care.

- Access to resources: A lack of perceived support (physical and financial) was often cited as a barrier to change. When these resources were present, change was facilitated.

- Beliefs about the consequences of change: Fear that changes might lead to accidents or loss of independence was another barrier to change.

- Perceived support: Whether friends, partners or caregivers were supportive of changing care routines impacted decisions about making changes.

- Peer mentorship: Peer mentors were regarded as highly influential when it came to making changes to care routines.

- Knowledge of options available: When people aren’t aware of the options, they don’t know what changes are possible. Knowledge of options was viewed as empowering.

“One of the key barriers and facilitators for people living with SCI was around knowledge of care options and knowledge of ability to change care. That was a key factor that predicted whether people would make changes [to their bowel care routine],” says Claydon. “And for a lot of people, that knowledge piece comes from their healthcare provider.”

Because healthcare providers are often the ones making suggestions and discussing options for bowel management, talking to healthcare providers about the factors that influence how they support changes to bowel care for patients with SCI was a logical next step, according to Claydon. So, in continued partnership with SCI BC and local SCI clinicians, the research team interviewed 13 healthcare providers in BC who work with patients with SCI.

In the study, published in the journal Disability and Rehabilitation in November 2024, healthcare providers were defined as any professional directly involved as a member of a care team for an individual with SCI, including nurses, nurse continence advisors, physiatrists, dieticians, peer support workers, care aids, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists. Because SCI is a complex condition that requires an interdisciplinary care team, the research team felt a broad approach was needed to best understand the influence of healthcare providers on bowel care.

“One of our participants in one of the studies told us bowel care after SCI takes a village and I thought that was a really nice viewpoint,” says Claydon. “If you only go to, I don’t know, the experts, [like] the physiatrists, you might have missed a big chunk of that village, especially for people in more rural areas.”

The healthcare providers in the study expressed that being knowledgeable about bowel care and bowel management options was necessary to help patients with SCI change their care routines. They also stressed that time and teamwork were required to have conversations about changing bowel care, but that time was in short supply. Balancing competing tasks, attending to more pressing medical needs, and the nature of shiftwork are all challenges that healthcare providers face when it

comes to having conversations about bowel care.

“Resources are short. Appointment times are short. The healthcare system is under pressure. And what that means is that the most urgent medical concern is always the priority in any health care visit… which often means that the bowel care quality of life piece can be neglected,” explains Claydon.

While time and resources may be limited, participants highlighted the important role that peer support from community members with SCI can play in supporting changes to bowel care routines. Claydon also pointed out that sometimes bowel care choices are simply based on an individual’s financial situation or health insurance.

“We’ve learned from our work that sometimes bowel care choices are made not based on what’s the optimal choice, but what’s covered by insurance. And that coverage is going to vary in different provinces, even and in different countries,” says Claydon.

Another key finding of the study was that the relationship dynamics between the healthcare provider and the client can encourage or discourage conversations about changing bowel care. For example, if healthcare providers feel that having a conversation about bowel care will cause discomfort and negatively impact their relationship with their client, they may be less likely to engage in bowel care conversations. The social and cultural identities of both the healthcare provider and the client can play a role in shaping these dynamics.

Regardless, Claydon points to the importance of prioritizing and normalizing conversations about bowel care. “It’s important to have conversations about it regularly and to review it regularly so that when concerns come up, they can be addressed promptly and that that burden on quality of life can be improved,” she says.

Moving forward, Claydon is working with SCI BC to develop and evaluate resources to increase knowledge around bowel care. “We don’t just want to put resources out there and sort of say, ‘Okay, here’s the knowledge,’ but really be mindful to evaluate them,” she says. “Just because they’re well-intentioned doesn’t mean they’re going to land well or actually be helpful.”

But on the whole, she says, the research speaks for itself: “One of the key takeaways is that bowel care is a major priority for people with SCI, and if it’s a priority for people living with SCI, then it should be a priority for healthcare providers.”

Funding for Dr. Claydon’s study was provided by the Craig H Neilsen Foundation.

You can follow Victoria Claydon’s lab for updates at x.com/VClaydonLab.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Snowbirding

- Aging with SCI video series

- Entrepreneurship

And more!