It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a wheelchair in the sky!? Adaptive paragliding is gaining traction right here in British Columbia and we’re excited to tell you all about it.

With humble beginnings in military parachuting, paragliding is a relatively new sport. In World War I, soldiers practiced landings by holding a tow rope while a truck accelerated until they floated. With practice, some soldiers found they enjoyed floating along air currents more than landing.

Canadian Domina Jalbert patented the first gliding parachute in 1965. He refined his design in subsequent years, creating the ram-air parachute or parafoil, an aerodynamic parachute broken up into cells. Air “rammed” into the cells, inflating the parachute. In the decade following, French engineer Pierre Lemongine and NASA scientist David Barish advanced the technology. In June 1978, Jean-Claude Bétemps, André Bohn, and Gérard Bosson determined that a ram-air parachute or “wing” could be inflated by running down a hill. They successfully launched from a 1000-metre elevation in Mieussy, France.

Since those early days of invention and exploration, paragliding has come a long way. Not to be confused with sky-diving, paragliding involves launching from a high elevation, typically a mountain. A pilot uses wind currents and air thermals (columns of rising warm air) to gain altitude and stay in the air for long periods of time. The length of the flight varies depending on the pilot’s skill and weather conditions. At the competitive level, pilots can remain in the air for as long as eight hours! Paragliding can be done solo or in tandem, allowing the novice passenger to enjoy the ride while the trained pilot controls the wing.

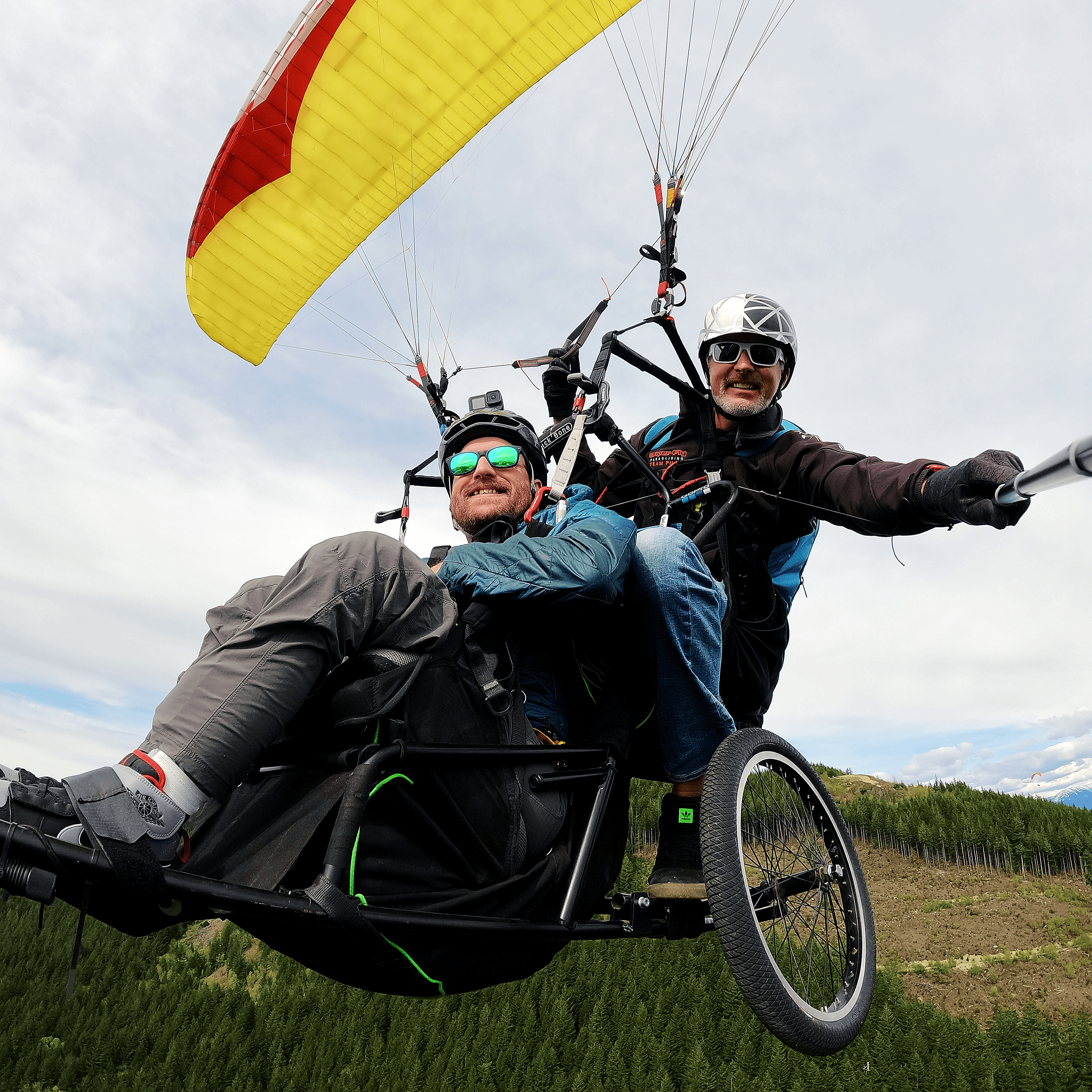

Adaptive paragliding uses a specialized chair (sometimes called a trike or rig) with an integrated harness to safely fly passengers with mobility challenges that prevent them from flying using the traditional foot-launched method. The Handivol flight chair is currently the only available flying chair designed and certified specifically for use in adaptive paragliding. Manufactured exclusively by French company Back Bone Paramotors, the chair costs approximately $6,700 Canadian dollars. The wing itself is the same used by able-bodied foot-launching pilots. With the Handivol flight chair weighing about 45 pounds, adaptive paragliders typically need to opt for a medium-sized wing.

Taking Flight

Intrigued? Well, now you have the chance to try adaptive paragliding close to home, thanks to one man’s bucket list.

David Stanek came across paragliding during unusual life circumstances. Seeking safety in Austria, Stanek, his wife, and 2-year-old son fled from war-torn Yugoslavia. A group of paragliders in the mountains directed them to train tunnels that crossed the border for their escape. The idea of paragliding lingered in Stanek’s mind. In 1992, he finally had his chance to try paragliding. Thousands of flights later, he hasn’t looked back.

“When you take off and you fly, everything goes away,” explains Stanek, who now lives in Chilliwack. Paragliding was his escape from the stress of running his own construction business. “[Paragliding] is not really physically demanding. It is more of a mental game. You have to pay attention, but yet you can be relaxed. Two hours later you land, and you think ‘Wow, I thought about nothing else but flying for those couple hours.’”

With his company now in the hands of his oldest son, Stanek is pursuing a long-time ‘bucket list’ goal of his. In May 2024, Stanek and his team launched Adaptive Airtime Paragliding, a BC-based non-profit organization dedicated to breaking down barriers and making the experience of free flight accessible to everyone. Whether you have an SCI, brain injury, mobility limitations, or any other kind of limitation, Adaptive Airtime wants to help you soar! Although able-bodied himself, Stanek says, “I came from a place where freedom was priceless. Flying is freedom. I think it’s important these days to give back a little bit. Everyone talks about diversity and inclusiveness. When push comes to shove, some people just don’t want to be bothered. I’m really on the receiving end because I meet amazing people.”

Stanek’s decades of flying, piloting, and teaching experience have introduced him to some incredible people, including American Chris Santacroce. An SCI halted Santacroce’s career as a full-time paragliding professional and Red Bull athlete. Santacroce’s experience inspired him to start Project

Airtime (projectairtime.org), a Utah-based non-profit organization providing free paragliding for people of all abilities for over ten years. “I was watching Project Airtime for years and how they built it up,” explains Stanek, “They are just amazing and support me a lot as well.” In fact, the team came out to Mount Woodside in Agassiz, BC at the beginning of May for Adaptive Airtime’s launch event, ‘Wheels Up’ Flying Weekend. Now that’s what we call teamwork!

So, what is adaptive paragliding like? We chatted with a few peers about their experience taking to the skies.

Rob Gosse

When Rob Gosse discovered the opportunity to paraglide was right in his backyard, he knew he had to try it. The Langley man is a self-described “adventure seeker”, having competed at the international level in adaptive alpine skiing and adaptive waterskiing. In May 2024, he signed up for Adaptive Airtime’s launch event.

“First of all, we arrived at the parking lot and got a rundown of what’s going to happen. We loaded up, went to the launch site, and chilled out. We watched some people take off to see the basics of how it’s done. They explained the equipment and how it all works as they’re taking off. It was a long process to get loaded in and hooked up, just making sure all the safety checks were done and everything was right. We waited a few cycles before the proper wind came up. There were two guys launching the two of us [Gosse and the tandem pilot]. Once we got airborne, it was such a cool feeling, feeling the lift, feeling the flight, and soaring with the eagles.”

“Working in Chilliwack, I recognized some of the sites. It looks so tiny up there and the cars looked like ants on the freeway down below,” Gosse explains. Overall, the tandem flights last around twenty to thirty minutes. If you’re hesitant, Gosse recommends that you, “Talk to David [Stanek] and watch some of the launches. We use this process when I coach water skiing. Just being able to see what happens takes the unknown out of it.”

Gosse has tried his fair share of adaptive sports and adaptive paragliding earns his stamp of approval. “Aside from the launch and the cleanup at the bottom, you could really be independent with it from right in the air and flying around,” he says. And Gosse is glad he’s found another activity he can do with his family. “I took my family, and we spent the day up there. It was a cool experience because they were able to fly as well. I was landing, my girlfriend was launching, and her son went before us, so we cycled through.”

Caleb and Andrea Brousseau

Caleb Brousseau brings a unique perspective to adaptive paragliding. After his L1/T12 incomplete SCI in 2007, Caleb enjoyed activities like whitewater kayaking and ski-racing, even competing on the Canadian Para-Alpine Ski Team. While mountain biking in 2020, Caleb sustained a C5 compression at the cervical level. Transitioning from paraplegic to quadriplegic with his second injury, Caleb began to wonder which sports he would enjoy. “For someone like me that’s a C5 level, there’s not a lot of sports left that have that full range or full ability left in it. Going mountain biking again, it doesn’t feel the same as mountain biking before.”

Then came paragliding. “Paragliding is something I’ve always thought about doing and never really had the opportunity to do it,” he says. When the opportunity to participate in adaptive paragliding in Colombia arose, Caleb hopped on a plane.

So, how did Caleb find adaptive paragliding as a quadriplegic? “With paragliding, so far, it still feels like I was a low-level para or an able-bodied person out there flying. It’s cliché to say, but I definitely didn’t think after the second accident that I’d find another sport that would have that ability in it. As a para athlete before, I thought I knew most of the sports that would have that feeling in it. And paragliding is one that does.”

Caleb enjoyed his first taste of paragliding so much that he convinced his wife, Andrea Brousseau to travel from Terrace to Agassiz for Adaptive Airtime’s launch event. Andrea says, “Honestly, Caleb was the one who was super excited about it. It’s something that I’ve seen around, but I never felt a deep desire to try it out. I already had the sports that I felt settled in and I wasn’t really sure how that sport would be adapted.”

Andrea, an above-the-knee amputee, is an impressive athlete herself. Competing in alpine skiing since she was a kid, Andrea represented Canada at the 2010 Paralympic games. She also enjoys ocean and river kayaking, cycling, spin biking, yoga, and, more recently, mountain biking.

When Andrea arrived at Mount Woodside, she had a lot of questions. “How does this work? How hard is the landing? Should I do this outside of the adaptive rig or just with the prosthetic? David [Stanek] and I talked it over. With the limitations of the prosthetic in terms of shock absorption, we decided I should go in the actual adaptive rig. He was really open. At no point did I feel pressured or worried.”

With their background in outdoor sports, both Brousseaus know the importance of safety and risk management. Andrea explains, “We talked through what makes it a good or bad flying day. It’s important to not push boundaries around that and to respect the conditions around you, your ability, and your pilot’s ability. It was nice to see the levelheaded planning behind it.” Caleb points out, “There’s a nerdy side that I really enjoy. It’s very similar to skiing and nerding out over snow and different things for avalanche awareness.”

Caleb was pleasantly surprised to discover how learning created a sense of community. “Being brand new [to paragliding], I’m talking to everyone around me. They’re usually more than happy to talk about all the different things and what each cloud feature means and like what to look for in the sky. We’re constantly bouncing that knowledge around. The community that’s created around it is really cool.”

“I thought [launching] would be startling like a bungee jump, but really it was this gentle, cruising, floaty feeling where you’re supported and then all of a sudden, you’re lifted off

the ground,” recalls Andrea. Both enthusiasts agree that paragliding feels similar to powder skiing. Caleb says, “It has that very Zen and slow feeling, which is really cool… We did fun little air acrobatic stuff where you do very light spirals and turns back and forth, which have a bit of G-force in them.”

Andrea explains that paragliding is, “one of the few sports that I think would give you exposure to that level of freedom and movement and flow that seems to come from sports that maybe aren’t quite as accessible once you have a physical disability. Give it a try because it is surprisingly liberating. It is absolutely a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

Any worries the pair had about landing were quickly eased. “It’s kind of like landing on a pillow,” laughs Caleb, “Landing with the trike is less rough than using a power chair on your normal sidewalk.” Andrea adds, “It was a surprisingly soft and gentle landing compared to the many times that I’ve hit the ground in other sports. The seating itself seems to be made to absorb shock.”

Brenden Doyle

Flying comes naturally for Brenden Doyle. Born and raised in California, Doyle joined the US military straight out of high school and served for nearly nine years. A skydiving accident caused a T11 complete SCI, but Doyle was determined to get back in the sky. “I contacted Project Airtime and got involved with Chris Santacroce and learned to fly with them. And I’ve been flying ever since.”

In January 2024, Austrian-based non-profit organization, Wheels4Flying organized the first international paragliding meeting and World Cup competition for paragliding pilots with reduced mobility. Doyle joined eighteen pilots in Piedechinche, Colombia for the event (in fact, this is where he met Caleb!) He hopes to return to Colombia in the future for the next event.

According to Doyle, paragliding is, “all dependent on where you want to take it.” As, “an avid skydiver with hundreds of jumps,” Doyle says, “I was flying solo within the first few days

of training. I’ve come from that background, so I picked it up fairly quickly.”

Although most people won’t have Doyle’s background in air sports, Adaptive Airtime’s Stanek stresses that, “if someone has the proper mindset and determination, they can absolutely fly solo.” The first step in learning to fly solo is ground school. You’ll start in a field and practice launching, staying afloat, and landing and work your way up to small hills. Stanek estimates ground school will take a week for most people, followed by a couple months of flight practice under the supervision of a trained pilot. Unsurprisingly, all the peers we chatted with are excited to learn to fly solo.

On The Horizon

So, what’s next for Adaptive Airtime? Stanek and his small but mighty team are gearing up for more events, fundraising, training, and community-building. “We are raising money, so we don’t have to charge anyone anything. We provide all the tandem flights and ground school for free. When we fly

companion people, like family members, we ask for donations to support the cause. All the proceeds go to equipment and instructors so we can keep doing this.”

Adaptive Airtime has big plans for adaptive paragliding in BC. “My goal is to create a network of schools and outlets for adaptive paragliding, so people don’t have to travel that far for tandem and make it accessible for athletes who want to learn to fly solo,” shares Stanek. And, so far, the response from the paragliding community has been incredible. The Adaptive Airtime team is actively working to build connections with every paragliding school in BC and to train their pilots to fly tandem with the trike. Experienced foot launch tandem pilots can complete training in as short as one weekend.

In June 2024, Adaptive Airtime joined forces with the West Coast Soaring Club to create what Stanek describes as a, “world class take off area which is much safer for adaptive tandems and solo flying.” Nearly 6,000 square feet of artificial grass was installed to create a smoother and larger launch area at Mount Woodside in Agassiz.

For peers who want to learn to fly solo, Stanek hopes Adaptive Airtime can be the stepping stone. “We will do the hard part, one-on-one ground school and first flight. And then we will send pilots to their area to local paragliding schools to teach them the progression to next level.” They also plan to fundraise for flight chairs for aspiring solo pilots. Stanek says, “The chair is the limitation. And I want to eliminate that limitation, because [able-bodied] solo pilots don’t have to buy chairs.”

Springtime marks the start of the flying season, so you can expect more events and opportunities from Adaptive Airtime in the coming months. To stay in the loop, you can check out

Adaptive Airtime’s website (adaptiveairtime.com) or follow them on Facebook (@Adaptive Airtime) and Instagram (@adaptiveairtime). And if you’re interested in booking a flight or have questions, simply fill out the contact form on their website and Stanek himself will get back to you.

Stanek has one final piece of advice. “I love flying tandem because no one is ever disappointed. Just sit, take selfies, and smile.”

Photo credit: “Special thanks to Rareborne Media and Crew for their creativity, images, production services.”

This article was originally published in the Summer 2024 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Artificial intelligence

- Nutrition

- Partner exercise

And more!

Read the full Summer 2024 Issue of The Spin online!