What would you think if I told you that, until recently, scientists and physicians generally assumed that women’s bodies worked like smaller versions of men’s? Decades of scientific research has been mostly based on male physiology, guided by the assumption that—aside from the obvious reproductive differences—male’s and female’s bodies function in much the same way.

But as it turns out, there are differences—and they do matter. And while the scientific community has made progress in understanding these differences and their implications for female’s health, a significant sex and gender gap persists.

For example, between 2009 and 2020, only 5.9% of research funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Canada’s federal funding agency for health research) looked at outcomes specific to women. And the research that does exist often overlooks differences in how male and female experience a wide range of conditions, resulting in a limited understanding of female’s symptoms and outcomes.

In the SCI community, research investigating sex and gender differences is even harder to come by. According to Dr. Alexandra Williams, a Postdoctoral Fellow at UBC’s Faculty of Medicine and the International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries (ICORD), one of the main challenges for researchers who study SCI is the relatively smaller number of women compared to men in the SCI population. There are about 86,000 people with SCI in Canada, and one-quarter of them are women. “The reality is that there’s a larger proportion of males in the SCI population, so it can be harder to find enough females for research studies,” says Williams.

Even so, the low ratio of women to men in the SCI population doesn’t fully explain the underrepresentation of women in SCI research. For example, a review of research on SCI and heart system health published in 2021 showed that women represent only one-eighth to one-quarter of study participants. And in many cases, the authors of the review noted, females are excluded from participating in clinical research (in favour of easier-to-recruit males) to make the study population more homogenous, and thus, easier to draw conclusions from. As a result, we know a lot more about the physiology of males with SCI compared to females.

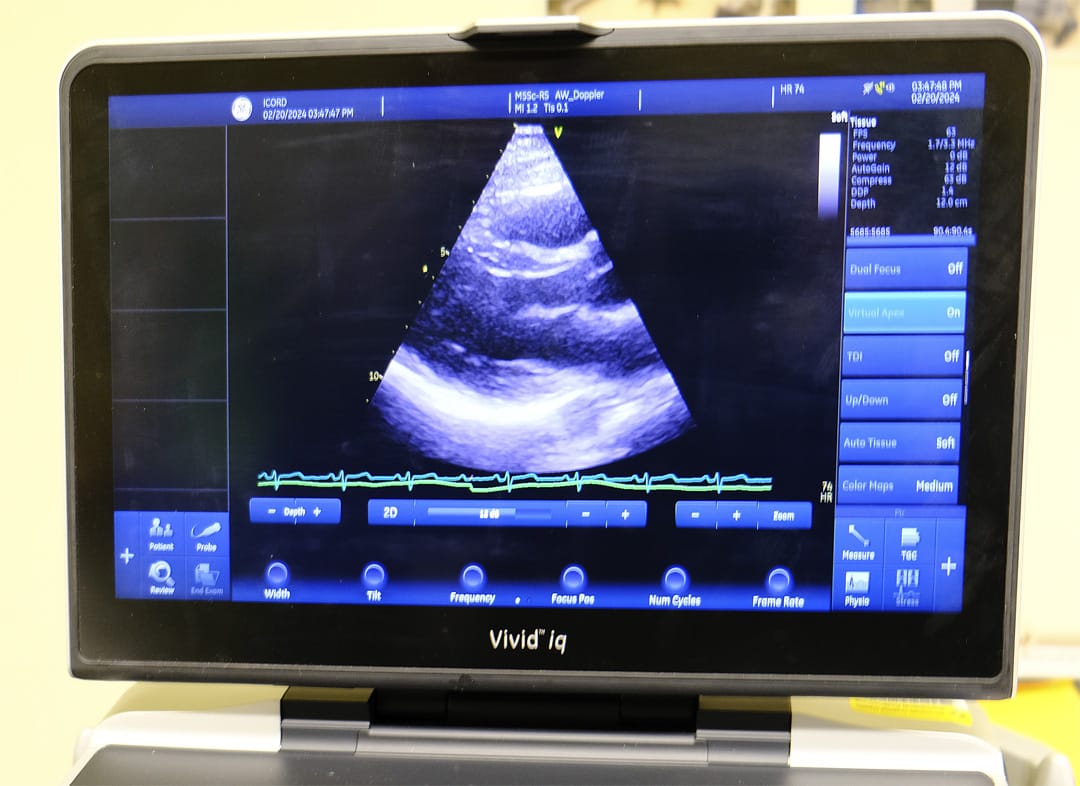

Williams drew similar conclusions from a review she led that focused on studies that used echocardiography, or heart ultrasound, to assess the impact of SCI on heart function. “We did a systematic review back in 2019, and from all the data we accumulated through those studies, about 5% of those data were from females. It was a very small percentage,” she explains. “And we thought, ‘Okay, there’s a huge gap in knowledge here.’ We’re not even scratching the surface of understanding female physiology in the context of SCI.”

This gap in knowledge is what led Williams to the world of SCI research. Before joining ICORD, Williams’ PhD research focused on understanding why the heart differs in its function and structure between males and females who are healthy, uninjured, and without any cardiovascular disease. According to Williams, there are differences in the size and shape of male and female hearts that are independent of body size. For instance, males tend to have larger hearts relative to the size of their body compared to females. Another key difference lies in how male and female hearts respond to stress. When standing up from a seated or lying position, females regulate their blood pressure in different ways than males, and can be more likely to faint as a result.

“But then the question is, ‘Why are females responding differently?’” says Williams. “And a key thing that we found in my PhD studies was that differences in male and female heart function are likely linked to their autonomic nervous system.” The autonomic nervous system regulates involuntary body processes—the processes that we can’t consciously control—such as heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing. It was this finding that prompted Williams to extend her PhD research to the SCI population.

“We’re bringing this research to a population that has a hugely impacted autonomic nervous system,” she explains. “And we’re wondering: Do those differences continue to occur in males and females with SCI? What are the repercussions of that loss of neural control of the heart? And will those baseline differences between males and females affect those outcomes?”

Williams is working with UBC Associate Professor and ICORD Principal Investigator Dr. Chris West, who studies the impact of high-level SCI on the heart. What we know from research in this area is that SCI at or above the mid-back impacts the way a person’s brain communicates information to the heart through the autonomic nervous system. In the case of high-level SCI, the heart and cardiovascular system can’t respond as adequately or effectively to a stressor, such as a change in posture or transitioning from rest to exercise, as they would prior to the injury.

The result, as many of our readers know, is that blood pressure management can be a challenge after SCI. People with SCI are also at increased risk of developing heart disease compared to the general population. Given the differences between male and female hearts that we know exist before injury—and their links to the autonomic nervous system—research focused on how male and female hearts function after SCI provides crucial insight into gender-specific treatment and management of issues related to the heart. With that end goal in mind, Williams and West are conducting a study to examine if there are differences in the hearts of males and females with SCI between the C4 and T6 levels when compared to the differences that exist between uninjured males and females. This will be the first study to investigate if there are differences between the male and female heart in people with SCI, and how potential sex-related differences play a role in blood pressure control.

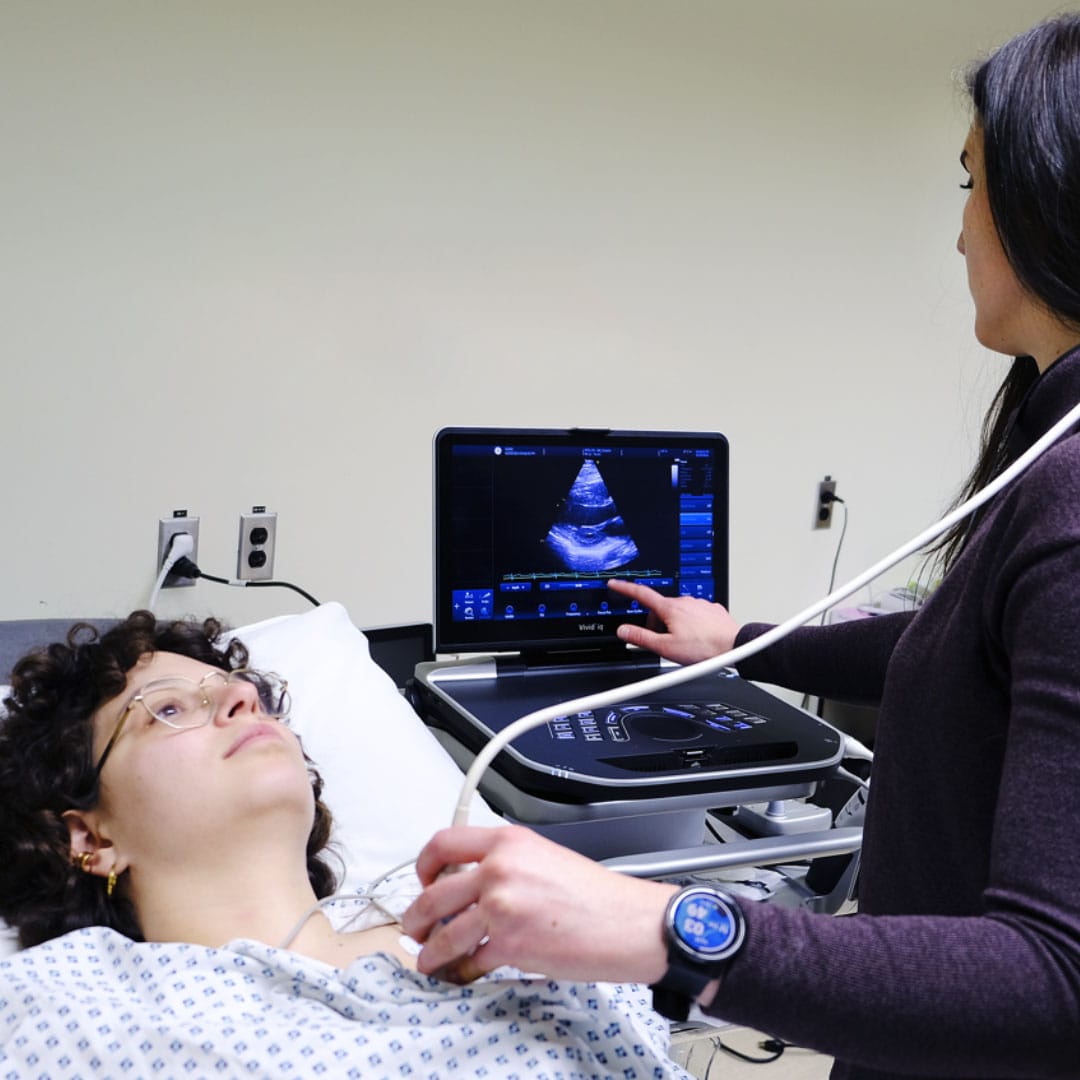

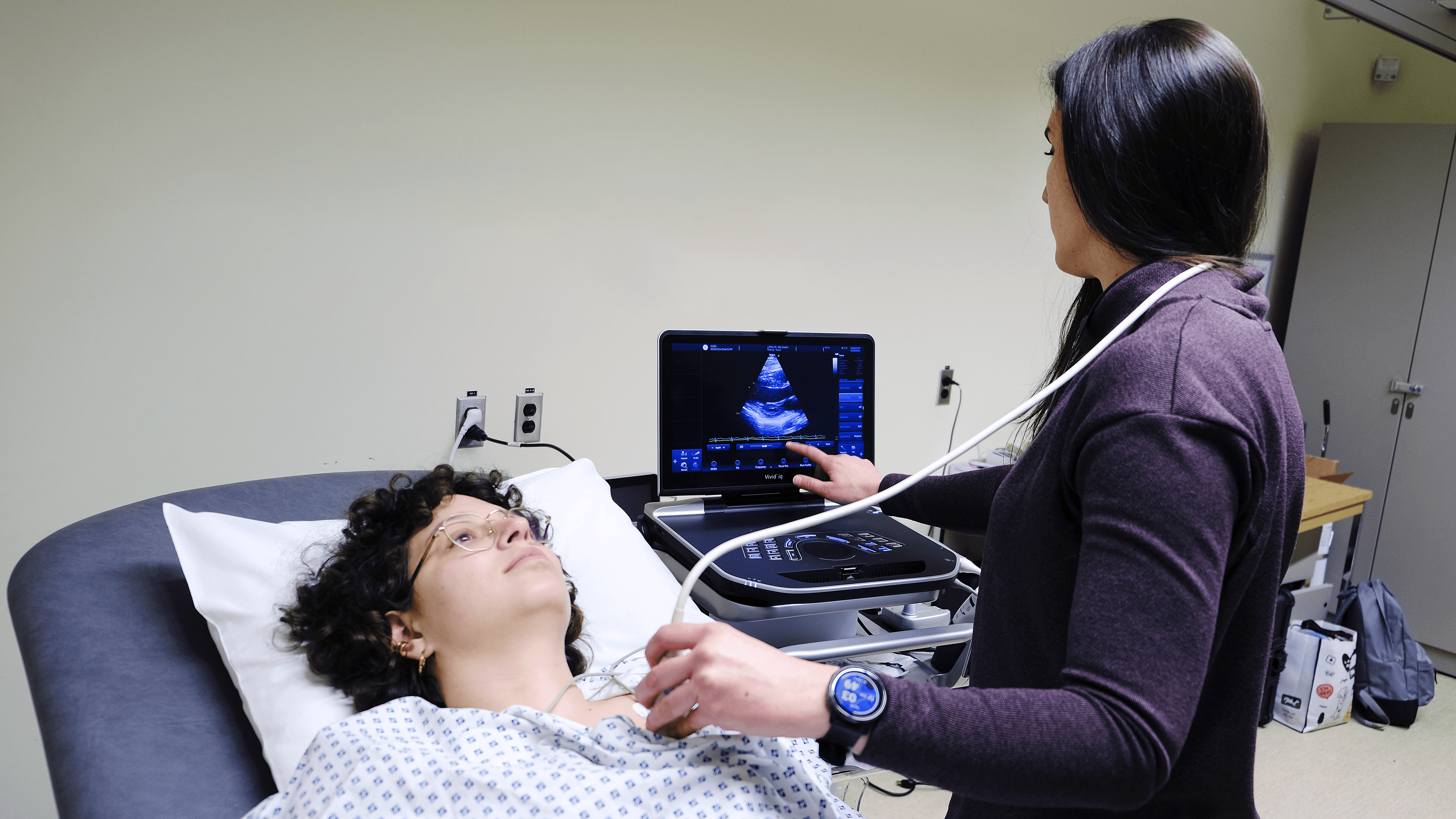

“It’s a pretty straightforward study. We have the individuals come into the laboratory at ICORD [in Vancouver] for just for a single day. The visit lasts about an hour and a half to two hours. We show them the equipment and measure their body weight. And then we have them transfer onto a tilt table for the tests,” says Williams.

The tests involve basic ultrasound scans of the heart to look at its size, shape, and function. At the same time, blood pressure is monitored using a standard arm cuff. The tests begin with the participant lying flat, allowing the research team to assess the heart at rest. From flat, the table is gradually tilted upwards so that the participant’s head is higher than their feet. Then the table is returned to a flat position before being tilted downwards so that the participant’s head is lower than their feet. Throughout this protocol, the research team continues to take scans and monitor blood pressure to examine how the heart responds to the changes in posture.

The research team has also worked to create a safe space for females who want to participate. “I’m the person doing the ultrasound testing,” says Williams. “And that is really helpful for women who are coming in because they often feel a little bit more comfortable with a female who’s scanning.”

The study includes four comparison groups: males with SCI, females with SCI, uninjured males, and uninjured females. Data collection is currently underway, and Williams is actively seeking males and females who have been living with SCI (between the C6 and T4 levels) for at least one year to participate in this study. To be eligible, you must be between the ages of 18 and 45 with no symptoms or history of heart disease. You’ll also need to be able to travel to the Blusson Spinal Cord Centre at ICORD (818 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver) for the assessment.

“I think this study is a really great starting point because we’re understanding not just resting function, but also function under stress, which is really important for understanding day to day challenges with blood pressure control,” says Williams. “We’re also hoping that this research will provide a foundation for understanding cardiovascular dysfunction, treatments, and long-term risks associated with SCI that could potentially be different in men and women.”

For Williams, this study is the first step toward understanding not just female heart function, but female physiology more generally, in the context of SCI. It’s about closing the sex and gender gap, one piece of knowledge at a time.

Click here to learn more about the study. You can also reach out to Alexandra Williams at alex.williams@ubc.ca for more information and to sign up. In the meantime, we’ll keep tabs on how the study progresses and report back when the findings come to light.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2024 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Camper trailers

- Peers’ experience of caregiving

- New research on pressure injury treatment

And more!

Read the full Spring 2024 Issue of The Spin online!