The Fall issue of our The Spin magazine will be out in a couple of weeks. In the meantime, here is my editorial from this issue. As always, I’d love to know what you think about my thoughts.

A recent headline caught my eye: “Nasal Cell Transplant Leads to Snotty Spine.”

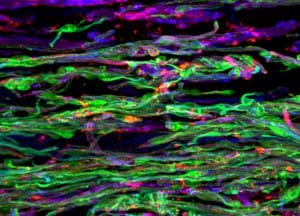

The medpagetoday.com article described the development of spinal cysts that actually produced mucous in a 28-year-old woman who had received olfactory stem cells to treat her SCI sustained ten years earlier. The treatment did not lead to any benefits, and now appears to actually have done harm (more on this will be found on page 15 of the Fall Spin and in the original Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine article). This and similar reports of stem cell treatments leading to tumour formation and other health issues should send up a warning flag to those hoping to receive similar, unproven treatments. Not only will these treatments require large sums of your money, they involve real health risks. And they’ve never been proven to lead to meaningful improvements in function after SCI.

It should also give researchers pause before rushing new cell-based and drug treatments into human trials. Most researchers will admit that SCI treatments currently being trialled in human subjects, and those in the pipeline, are unlikely to lead to significant improvements. But they add that these trials are critical for establishing better research processes, so that when more promising treatments are developed, they’ll be better able to quickly evaluate their effectiveness.

Is this a valid reason to be rushing treatments into clinical trials? What is the cost to people who are expecting more significant benefits of the research? Also, a lot of money is being invested in these trials—is it well spent?

Readers may remember my recent call for a resetting of the balance between research funding and services that improve aspects of daily living. I also believe we need to reset the balance of funding within the continuum of SCI research. Yes, basic research is critical—we need novel interventions, technologies and practices that will have long and medium-term impacts for people with SCI. But there is much more to research than stem cells and drug development.

That’s why we’re proud community partners with many leading research centres, such as ICORD and the Rick Hansen Institute, with which we’re involved in projects ranging from improving cardiovascular health to developing better information resources and practices concerning perinatal issues for women with SCI.

We’re also partnering with the research team at McMaster University’s SCI Action Canada group to investigate the important role of peer mentorship and leadership in enhancing community participation and quality of life for people with SCI. We’re very proud of our role as a lead investigator on a new, $2.6 million project funded by Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Over the next seven years, we’ll seek to understand the best ways to enhance the quality and quantity of community participation amongst Canadians with disabilities, with a specific focus on employment, mobility and physical activity. This project, led by Dr. Kathleen Martin Ginis at McMaster University, engages over 20 researchers and 20 community service organizations throughout Canada in research that will lead directly to positive social and economic benefits, not only for people with disabilities, but all Canadians.

No, it’s not a cure. And yes, research may eventually lead to a cure, and we need to continue to support it—but not at the expense of research that can have more immediate impacts. I’ve heard from many of my friends with SCI that they need not be cured to be whole. So true. But there is a lot research can do to enhance opportunities and well-being for people with SCI.

Perhaps this is a better investment than a snotty spine?