Peer support is powerful, but peer health coaching takes it to the next level. It’s a practical, evidence-based program built around real conversations where lived experience meets professional training. Let us tell you how it began and where it’s headed.

The Coaching Evolution

More than two decades ago, John Shepherd’s life changed in an instant. He hit black ice while driving home to Montreal from business school. At the time, he was planning a post-graduate move to London for a career in investment banking. Instead, he found himself adjusting to life with an SCI.

Shepherd says, “This was the most challenging single time in my life. I was more undermined in my ability to use my own resources to deal with stuff. You need more capacity than you’ve ever needed before, and you have less than you’ve ever had. It’s a really tough situation to be in and you’re undergoing this intense transformation.”

Eventually, Shepherd returned to business school and took a healthcare operations course that sparked his curiosity about SCI from an academic perspective. He began working with the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation, focusing on the development of an online SCI education platform. He also served on several boards and committees but found himself wanting more than just volunteer opportunities.

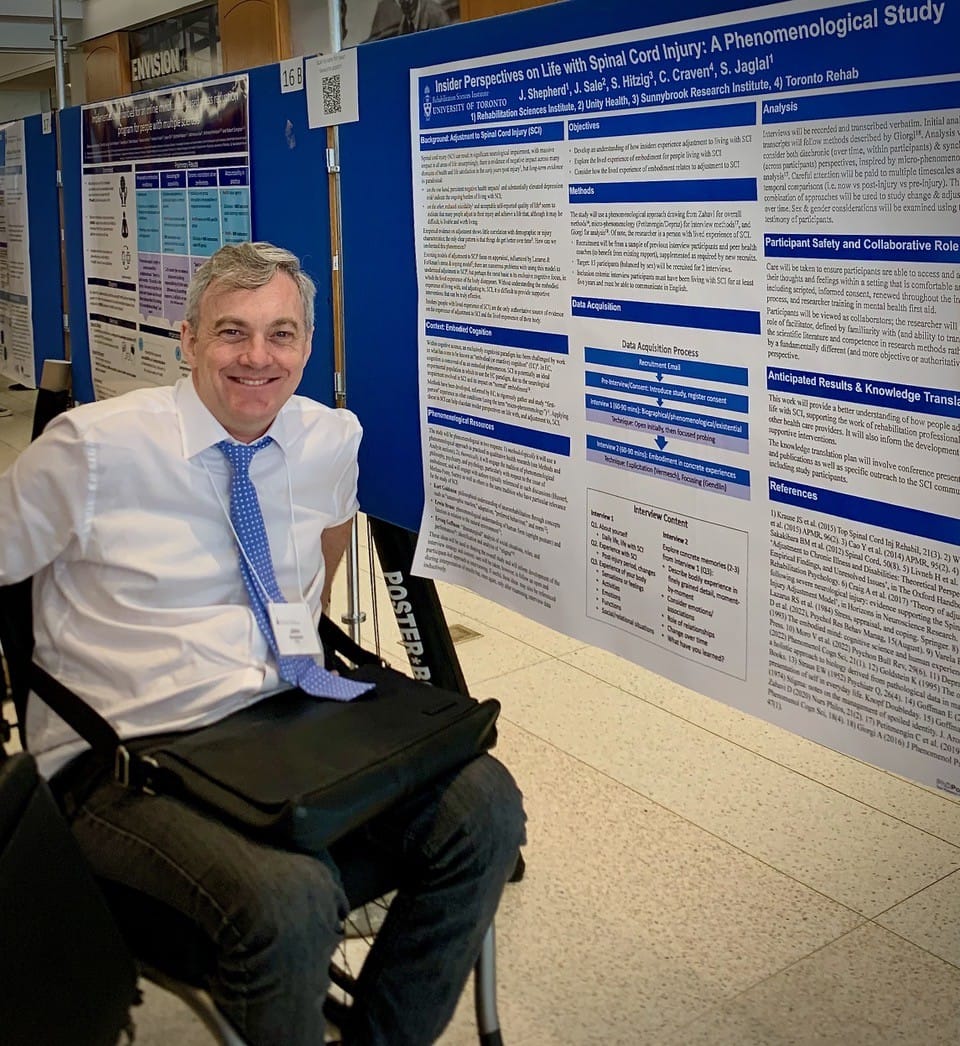

Determined to make a lasting impact, Shepherd pursued a PhD at the University of Toronto, blending personal experience with research. For him, studying SCI isn’t just a career—it’s a way to reframe and explore a life that is often misunderstood. “Living with SCI is typically conceived of as a frightening thing,” Shepherd says. “Without negating the truth of any other perspectives, I am focused on how it’s a fascinating experience to have and to look into. Perhaps all the more fascinating because it is so rarely looked into precisely because of the fears and anxiety around it.”

The SCI&U Peer Health Coaching Program he now helps lead is the result of years of collaboration. Its earliest form came from Sarah Skeels at Tufts University in Massachusetts, who created a telephone-based peer coaching model called My Care, My Call. Skeels worked closely with the BC-based Center for Collaboration, Motivation, and Innovation (CCMI).

Around the same time, Shepherd and his supervisor, Dr. Susan Jaglal, were developing a similar project. They launched a Canadian pilot of SCI&U, adapting My Care, My Call into a video-based peer coaching model. Barry Arana, now SCI&U Research Coordinator and Peer Health Coach with SCI BC, was there from the start: “I’ve been part of the SCI&U Peer Health Coaching study from the very beginning and [have] seen how it’s evolved over the years. We started off with just 10 participants in the first stage of the study.”

After the successful pilot, the team expanded SCI&U into a larger, 60 person randomized controlled trial, in partnership with SCI BC. A smaller, parallel trial also took place in the U.S. Over six months, participants showed improvements in health self-management. The gains were especially strong among those who had strong social support, were between one and six years post-injury, identified as white, were male, or had tetraplegia. The program also boosted life satisfaction, awareness of services, and overall service use.

Today, a new version of the SCI&U study is underway, this time focusing on people who are newly injured—within the first two years post-injury. The goal is to see how early support might make a bigger impact.

Teri Thorson, SCI BC’s Manager of Peer Coaching and Outreach, was also part of the initial SCI&U study. “With research, when the funding ends, it ends,” explains Thorson. “I felt passionate about this project, so thankfully, [SCI BC’s Executive Director] Chris McBride saw the benefit of the coaching studies. Physios at G.F. Strong also felt that it was of value to peers.” SCI BC’s Peer Health Coaching Program was developed and is now open to anyone in BC with an SCI or related disability, regardless of your age, location, mobility, or time since injury. You may have read about it in the Goal Getters article in the Spring 2024 issue of The Spin. Here’s a closer look at how peer health coaching works and why peers find it so helpful.

Self-Management

The peer coaching model is simple, but powerful. Trained Coaches living with SCI meet with peers by video or phone regularly. Coaches help peers set meaningful goals, develop self-management skills, build confidence, and access resources needed to live well with SCI.

In healthcare, self-management refers to a person’s ability and willingness to take on the daily management of their health care. That includes managing symptoms and treatment, maintaining routines and roles, coping with emotional challenges, and navigating the healthcare system.

For Shepherd, self-management is a useful term because it’s a recognized concept in healthcare. Using familiar language helps researchers open doors and move new ideas forward. But he sees Peer Health Coaching as much more than self-management: “The full scope of what we’re doing is helping people learn how to live with an SCI and that’s important and underrecognized.”

He points out that before World War II, people with SCI rarely survived long-term, let alone thrived. Since then, rehab systems have emerged, but they often fall short. He explains, “These experts, almost without exception, are people who don’t actually live with SCI. They’re teaching something that, in a certain sense, they not only do not, but cannot, know.” And with rehab stays shorter than ever, often just several weeks, there’s little time to absorb the kind of lived, practical knowledge that can’t be found in books.

Programs like SCI&U formalize what peers have long done informally: sharing insights, tips, and encouragement that only someone who’s been there can offer. It picks up where rehab leaves off and, in many ways, fills in what rehab can’t provide.

Arana agrees, “As someone living with SCI, 14 years post-injury now, learning self-management skills is crucial and important to my livelihood and quality of life. Learning ways to better take care of yourself and building on your self-management skills can prevent hospitalizations, pressure sores, fractures, and UTIs. Honestly, the last thing I need as someone in a chair is other complications. I’ve learned so many things over the years, because I participated in research studies and attended events through SCI BC, ICORD, and the Blusson Clinic. That’s how I learned that you could treat neurogenic bladder with Botox. That really improved my life. It was huge to have another tool to better self-manage.”

More Than a Peer

“Lived experience is the raw material energy that powers the Coaching program,” says Shepherd. “What makes it really distinctive is the way that it’s refined through the training, the specificity of the role, and the way that the Coaches become experts in wearing different hats.”

In an early My Care, My Call study, Skeel and her team analyzed transcripts from over 500 coaching calls. They identified three roles Coaches take on: Supporter (building trust and confidence), Role Model (sharing lived experiences), and Advisor (teaching, strategizing, and action planning).

While Supporter and Role Model roles are common in peer mentorship, the Advisor role is unique to Peer Health Coaching. And the way Coaches shift between roles is critical. Early on, Coaches lean into Role Model mode to build trust. As participants grow more confident and ready to take action, they move into the Advisor role. The Supporter role remains constant throughout, helping participants build self-efficacy.

Coaches are well prepared for this. As Shepherd explains, “They’re extensively trained in a specific set of skills around Motivational Interviewing, Brief Action Planning, Mental Health First Aid, and the use of various tools in our coaching program.”

In addition to these 90 hours of training, Coaches role-play coaching scenarios and meet weekly to debrief. Shepherd likens this process to the clinical supervision used by mental health professionals.

“We’re intentional about making sure that the team is plugged into each other, well-resourced, and that we’re continuing the journey together,” says Shepherd. “We created an environment where [Coaches] feel their experience is not just valued but really forms the norm in terms of expectations and understandings.”

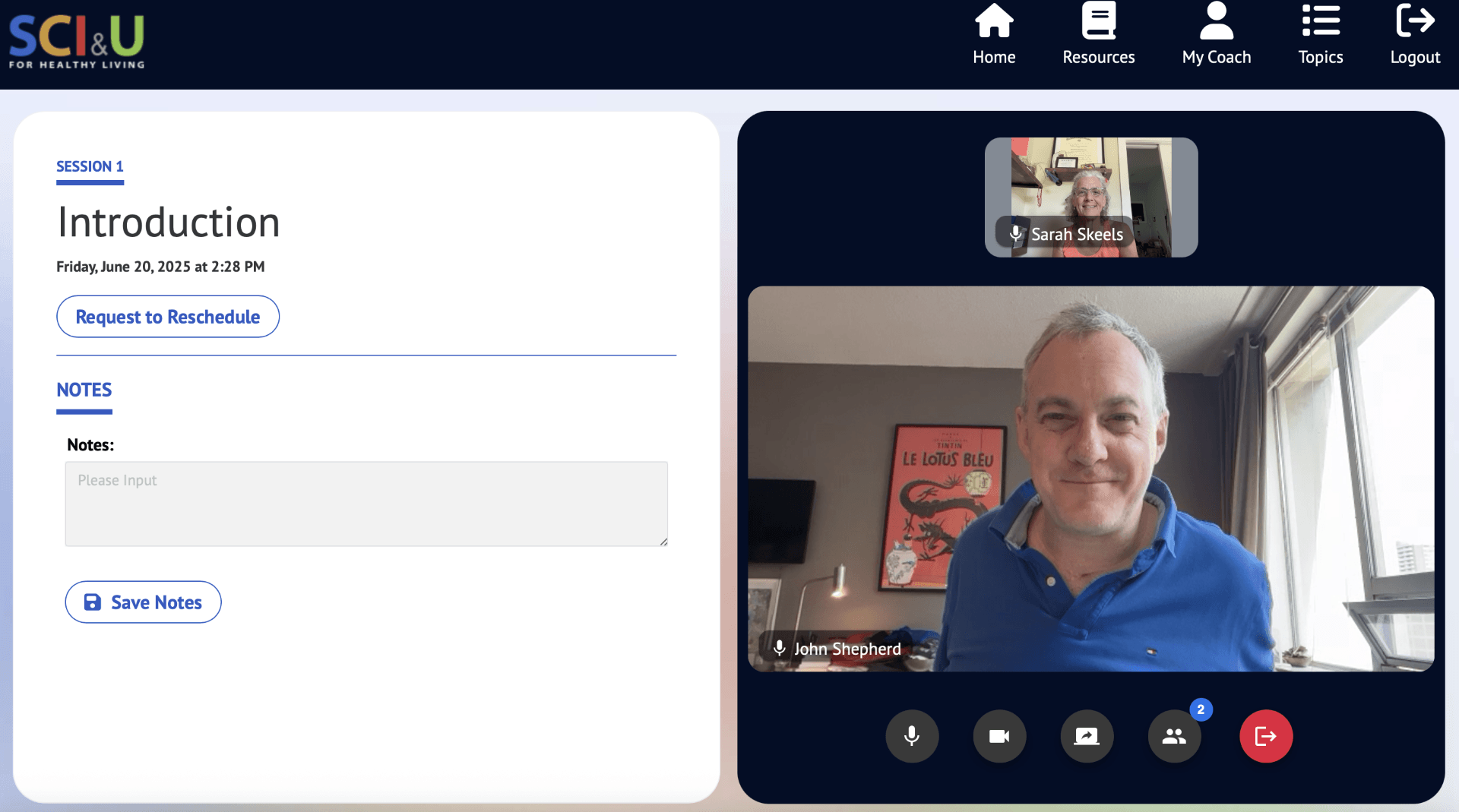

The current SCI&U program includes an online platform covering various health topics. Coaches use it to help participants find reliable information and learn practical healthcare skills, like preparing for appointments and talking with providers. The team updates the platform regularly.

“[The coaching platform] supports the interaction between coach and participant in ways that nourish and enrich that interaction. But ultimately the interaction is what matters,” says Shepherd. The goal is to eventually make the platform open source for use beyond SCI&U, including other peer programs.

The Right Ingredients

Peer coaching turns support into progress. It works because Coaches bring both understanding and structure, helping peers move from “stuck” to “started.”

While many participants focus on weight management, physical activity, or nutrition, goals can be anything. Thorson says, “It doesn’t have to be necessarily about health. Maybe it’s booking an appointment, as simple as that. It doesn’t have to be a big goal like losing 30 pounds. It can be a really small goal, and you can learn a lot about yourself by talking to someone who has expertise in Motivational Interviewing skills.”

If you don’t have a goal in mind, your Coach can help you figure out where to start. Arana says, “I consider it a win that they show up every single time to our coaching session. The fact I’m able to create a safe space for them to open up and share what they’re struggling with or want to focus on. The first step is saying ‘I want to work on this.’”

Coaching conversations are grounded in Motivational Interviewing, a communication style that helps people uncover their own reasons for change. Coaches use techniques like reflective listening, open-ended questions, and exploring personal values to guide the conversation.

Once someone’s ready to act, Coaches use Brief Action Planning (BAP) to break things down into actionable, manageable steps. BAP draws on tools like SMART Goals and structured problem-solving, but its real value lies in helping people feel capable. Shepherd explains, “You frame a problem as something that you have a tool to address, rather than as something that could potentially destroy your day or your life. That shift is, psychologically, incredibly important and empowering.” Coaches use the tools to offer structure, support, and accountability at the exact moment someone is ready to take a step forward.

Bryan’s Coaching Experience

For Bryan Anderson, peer coaching came at a pivotal time. “Life for me has changed a lot in the last couple years,” he says. A father of two teenagers and former heli-ski guide, Anderson sustained an SCI while body surfing on a remote island off the coast of Nicaragua. “I hit my head on the shallow sandbar and broke my neck. It was a bit of a show getting me home.” After major spinal surgery in Nicaragua, he spent months in ICU and rehab before returning home to Golden that fall.

The first winter was especially hard. “I was struggling hard with all the secondary complications. Back-to-back pressure sores and bladder infections and in and out of the hospital.” Living in a small town without much of an SCI community, Anderson felt isolated. “I’m one of two in a wheelchair, besides the elderly… trying to get outside in the snow, I struggled pretty hard.”

That’s when SCI BC’s Peer Health Coaching Program came in. Anderson says, “It really helped me with my confidence and coping.” His coach, Mary-Jo Fetterly brought lived experience and a background in yoga and massage therapy. “Mary-Jo was quite an incredible person to get connected with. We’ve been friends ever since.”

For Anderson, the biggest shift was internal. “Pre-coaching I was feeling useless, like a burden, and not feeling like I have anything to give back. I still get days where I feel like that for sure. Then I picture Mary-Jo in my mind, talking me through it, saying, ‘Just breathe. You’re loved. Take control of those feelings and use that.’ She helped me more than anybody navigating through that crazy head space.”

Anxiety became a regular challenge. “Since I broke my neck, I’ve had anxiety a lot and over the stupidest little things.” Coaching gave Anderson the tools he needed. “If you asked me about yoga a couple years ago, there’s no freaking way I would have sat down and made time. I come out of coaching more relaxed.”

Fetterly’s support helped both Anderson and his wife, Amie. “She was super helpful for my wife too. Really helped with both our headspaces and giving me tools and tricks to deal with the anxiety and my health.”

One of the most valuable aspects of coaching, for Anderson, is how personalized and responsive it is. “My health bounced back and forth week to week. But Mary-Jo could see I was frustrated and then would focus on that. It seemed to me, she would start a session with something in mind, but she would maneuver the session according to how she picked up on how I was feeling and my current frustrations.”

Coaching also helped Anderson rethink his habits. “Before my accident, I just ate whatever, whenever, I was very active. Now I eat food that I never would have eaten before.” He adds with a laugh, “I was a little heavy when I broke my neck, not because of eating so much, [but more so] my love for beer. Mary-Jo helped me safely lose a bunch of weight, which has made everything easier.” He also believes coaching has helped reduce the frequency of bladder infections.

Anderson adds, “You can tell when [your Coach] is talking, they have your interest 100%. They don’t drift. You can tell they’re not doing it for a job. They’re doing it to help people and that comes through right away. You can’t miss it.” Although Anderson’s coaching sessions have ended, he and Fetterly always catch up when he comes to Vancouver.

Why This Research Matters

Anderson’s experience shows how powerful peer health coaching can be, especially in the early days of adjusting to life with an SCI. But proving that impact through research isn’t easy.

Shepherd explains, “It’s tricky. Getting a new intervention and getting it taken up in practice is very difficult. All the more so when there are aspects of what you’re doing that cut against the culture of healthcare.” Peer-led coaching challenges the traditional divide between patients and providers, something many healthcare systems are resistant to change. And, while healthcare professionals have established authority and funding within the system, peer Coaches face a steeper climb, requiring more research, evidence, and effort to get programs like SCI&U funded and scaled up.

It’s also hard to measure. SCI has no single biomarker or universal metric for living well. Questionnaires like the Patient Activation Measure can help show improvements in self-management over time. But as we’ve seen, coaching is far more than self-management. It can prevent complications, reduce healthcare use, and build confidence, connection, mental well-being, and more! These benefits are harder to quantify and often overlooked by funders and policymakers.

That’s exactly why research like SCI&U matters. There’s no single number that captures the full impact. But by taking part in studies like SCI&U, participants help show the value of peer coaching and bring it closer to becoming standard practice.

Get Involved

We already know peer health coaching can be a lifeline. Research helps make it a reality for more people.

The SCI&U Peer Coaching Program is currently recruiting newly injured SCI peers (within two years post-injury) for a randomized controlled trial (RCT). If you’re interested or have questions, contact Barry Arana at barana@sci-bc.ca. If you’re not eligible for this trial, he will connect you with SCI BC’s Peer Health Coaching Program, which is open to anyone with a disability.

After screening, you’ll review the consent form and take part in a brief (about 10 minutes) interview about your health and goals, followed by a set of questionnaires. These questionnaires will be repeated at six months and one year to track any changes.

Because this is an RCT, participants are randomly assigned either to the coaching group or the control group. After six months, those in the control group will also have the opportunity to receive coaching. All participants receive a gift card honourarium.

Once matched with a Coach, you’ll meet via video or phone every one to two weeks for 8-14 sessions scheduled at times that suit you. Each session lasts approximately 45-50 minutes.

Ultimately, Anderson credits peer health coaching with providing the tools he needed to manage his SCI and rebuild his self-worth. “I keep reverting back to those coaching tips and techniques… Things I never thought about before, I’m now using and thinking about.” Peer health coaching fills important gaps by combining evidence-based practice with peer connection, reminding us that healing is often a shared journey, and no one faces SCI alone.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2025 issue of The Spin. Read more stories from this issue, including:

- Accessible gardening

- Treatments for fatigue

- Measuring peer support programs

And more!