This Ask an Expert series was created by Dr. Andrei Krassioukov and Spinal Cord Injury BC, with support by a grant from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation.

You asked VCH/Richmond Hospital’s Infectious Diseases Specialist Dr. Jennifer Grant all your questions, and here we’ve collected the main themes and resources shared in this latest Ask an Expert session. For the full list of questions and timecodes to skip to their answers, look for the list in the Description box below this video on Youtube.

Can COVID-19 Survive on Hard Surfaces? (6:10)

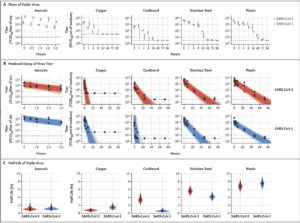

A recent experiment looked at surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 compared with SARS-CoV-1, the most closely related human coronavirus.2 . This article describes an experimental procedure using a higher concentration of virus than is seen in daily life. Dr. Grant says you can disregard the Aerosols column because it was done under experimental protocols that are unrealistic in real life. Take home message: The time it takes for the virus that causes COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) under experimental procedures to decay by half is highest for Plastic (6.8 hrs), Stainless Steel (5.6 hrs), cardboard (~3hrs), and Copper (~1 hr).

- Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1 N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1564-1567

How long can the virus stay on doorknobs and keyboards (11:11)?

Left completely unchecked with a large inoculum of virus (as used in the experiment, which is very unusual in real life), the virus could survive for up to 24 hours. This is even lower when exposed to UV light. If you are sharing your keyboard with other people regularly and can’t control who you are in contact with, clean your keyboard with a standard household cleaner, wash your hands after using a keyboard, or use a keyboard cover you can wash or change.

Doorknobs – it would depend on the material, however the virus tends to last longer on non-porous surfaces like metals. If you are in a place where other people are using the doorknobs and you can’t control their cleanliness, make sure to wash your hands afterwards or avoid touching doorknobs entirely.

Can COVID live on my wheels? (20:34) Can COVID get on my wheelchair? (18:14)

Wheelchair tires are made of rubber, which we would estimate would have virus surviving on it for a duration somewhere between plastic and a soft surface. Dr. Grant mentions that a tire running on the ground gets a lot of mechanical friction, making it harder for the virus to survive. Wheelchair wheels also have push rims which are usually aluminium sometimes coated with vinyl or another surface made of plastic and other materials and do not see the same amount of friction as tires do, so make sure to clean them when you clean your hands. Plastic and metal are surfaces the virus can survive for up to a day on, so make sure to wash your hands regularly and thoroughly and wash high-touch surfaces on your wheelchair with a household cleaner. Check out the handwashing guide for wheelchair users here: www.sci-bc.ca/handwashing

Remember, just having virus on your wheelchair or your hands will not infect you – it’s when you touch surfaces where viruses may exist and then touch your mouth, eyes or nose that the virus can infect you, so make sure to wipe your wheelchair down periodically and wash your hands regularly and ensure any caregiver is doing the same.

Should we (wheelchair users) be wearing gloves when out in public pushing our wheelchairs? (26:20)

If you need to for mechanical protection reasons, yes, You don’t want to get sores on your hands, but there’s no reason from an infection point of view. If you wear gloves the whole time, and you touch your face, mouth or nose, you still have to wash your hands, and gloves prevent the micro-immune system on your hands from protecting you. Taking off gloves is an opportunity for contamination (especially if you need to use your teeth to help you) so you’ll still have to wash your hands.

Have Quads in other countries had COVID-19? (27:13) What are the differences in risk between levels of injury, ie high quad, low quad, high para, low para. (21:53)

We don’t have enough data to really know definitively. The higher the spinal cord injury the more difficult it is to control your respiratory secretions. Those who require a trach/ventilator, are also at higher risk for pneumonia, and have less muscle function available in the chest for respiration. With injuries lower down on the spinal cord, the lower we go the less the risk, aside from the general risks of transmission for those who need close-contact caregiving.

Check out our first Ask An Expert session with Dr. Andrei Krassioukov, which has a more comprehensive discussion of immune dysfunction and risk factors for people living with spinal cord injuries. For a summary of what we know thus far about risk, immunity and SCI from published studies and COVID experience, check out the Spin Doctor article pictured here (from our June 2020 issue of The Spin, page 14).

There are two recent research papers describing COVID-19 in people with spinal cord injury from Italy and Spain, indicating that COVID-19 may show up with atypical symptoms or be obscured by SCI complications like autonomic dysreflexia.

- Clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a cohort of patients with disability due to spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Series and Cases volume 6, Article number: 39 (2020).

- Atypical Presentation of COVID-19 in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury Spinal Cord Series and Cases 2020:6:38

Risks of Transmission of COVID-19 from Kids/Grandkids

- I have a cervical injury and two school-aged children. Is it dangerous for my kids to go back to school before a vaccine is available? (12:43)

- If asymptomatic children bring back the virus to immunosuppressed parents what should we do? Should kids wear masks? (15:51)

- Is it safe for me to visit my grandchildren after they return from school if they have exposure to other people? (25:24)

- Are fewer kids infected by COVID-19 or just more asymptomatic? (29:20)

Kids are at much lower risk for COVID-19 (meaning they are less likely to get sick and produce mucus), and in places like Australia, even when they have had kids with active COVID19 disease at schools they seem less likely to transmit the virus. Several studies have indicated that even with children at school with virus circulating they didn’t see virus transmission to other kids or to adults. An Icelandic population study indicated that children were less likely to be infected: none of those who received screening tests (i.e. without symptoms) tested positive, and children under 10 in the targeted testing group tested positive at half the rate of children over 10 years of age. However, another study in Italy suggests kids get the virus as often as adults and that fewer cases are seen in kids because schools have been closed and kids haven’t been exposed to the virus as often. Masks are challenging with kids because most can’t follow the precautions needed to make mask use effective. For kids who are old enough to go along with regular effective handwashing, it is safe enough for them to go back to school, however, it’s a risk management question for you specifically – it may be a very long time before a vaccine is available. Resources mentioned:

Can you outline the process for developing a safe vaccine in Canada? (38:25)

- Candidate vaccine development in the laboratory (What substance/particle can we identify or create to provoke the human immune system to fight off COVID-19?)

- Test candidate vaccine in animals (Is this immune-provoking item dangerous?)

- Test candidate vaccine in non-human primates (Is it safe and effective in animals similar to humans? What kind of dose might be needed?)

- Phase I Trials: Testing for safety in healthy human volunteers (Is it safe for use in humans?)

- Phase II: Efficacy testing (Does it provoke an immune response in humans? How does it provoke the immune system? How should we dose it?)

- Phase III: Clinical trials in large groups of people (Does it do what we want it to? Can we identify any rare side effects? Is the immune response effective against the virus?)

- Regulatory review and approval by authorities (Health Canada, or in the US, the Food and Drug Administration, FDA)

- Manufacturing (How and where can this be produced in a high-quality, fast and cost-effective way? Can it be produced and distributed in a timely and effective way?)

- Quality Control (Is the vaccine giving reliable immune protection against the virus? Are there adverse events? Is the distribution system working?)

- Vaccines for Human Use in Canada. Health Canada.

- Drugs and Vaccines for COVID-19, Health Canada.

- Vaccine Testing and Approval Process. US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention