LIFE IN THE TIME OF COVID-19

Nearly four months into the COVID-19 pandemic, there are countless questions that remain unanswered. But one fact is indisputable: social distancing and isolation, along with strict hygienic practices, can lower the risk of contracting or spreading the virus.

That’s reassuring for the majority of individuals and families. But what about people who are absolutely reliant on daily support from caregivers for the most basic of needs? That’s the reality for many readers—people with higher levels of quadriplegia who face the double jeopardy of being potentially exposed because of their reliance on caregivers, and being at high risk for serious COVID complications because of their compromised immune and respiratory functions and other health issues related to their SCI.

We suspect this dilemma has elevated the anxiety levels of most SCI BC Peers who rely on caregivers — particularly after reaching out to three of them who fall into this category. Vancouver’s Barry Araña, and Victoria’s Joe Coughlin and Chris Marks, all agreed to share their experiences navigating the pandemic up to this point. We wanted to know if they managed to stay healthy, what their fear factor was, what steps they took to mitigate the risk, and how they’re preparing for a possible (perhaps even probable) second wave this fall and winter.

The good news is that all three have stayed infection-free—at least, to the best of their knowledge. The bad news is that they’ve all found the experience extremely frightening, and although they’ve been doing the best they could, they’ve all felt a loss of control, relying on improvisation rather than a firm plan. Not only that, they’ve all felt unsupported by government and our health care system. And despite the fact that all are doing what they can this summer to prepare for a second wave, they’re all dreading that possibility.

A STRESSFUL TIME FOR ALL INVOLVED

“I may be doing my part staying at home at all times, but my exposure is high because of my home support workers,” says Araña, a C-5/6 quadriplegic who receives about four hours of assistance daily from three different workers via Vancouver Coastal Health. “They visit multiple patients per day in the community; they take public transportation. There was an outbreak at Haro Park where over 20 home support workers tested positive for COVID. Learning this created paranoia for me. There’s no doubt that I was panicking about getting the virus from a home care support worker. But I have no choice but to continue using home support from VCH. I cannot function normally without the help of home support.”

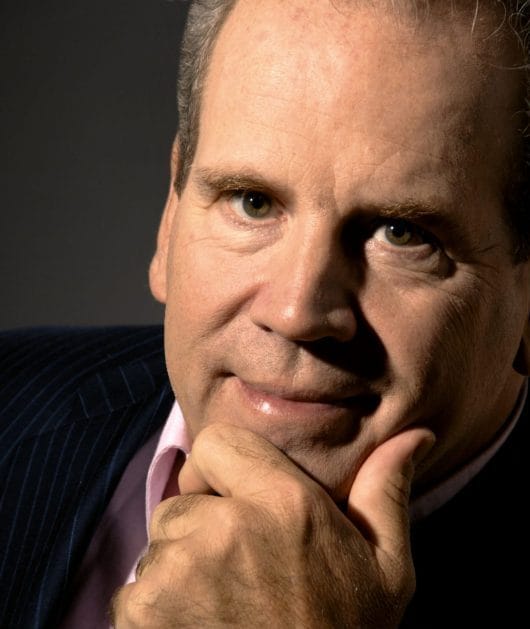

Coughlin, also a C-5/6 quadriplegic, agrees the pandemic has been incredibly stressful. “My anxiety level has increased tenfold, but whose hasn’t?” muses Coughlin, who self-manages his own seven hours of daily care via the CSIL program. “I’ve been flying by the seat of my pants. If anyone tells you that they were completely prepared for a global pandemic, they’re flinging bullshit. I laid off all my part-time staff back in late March, when the Medical Health Officer declared that HCAs could only work for one facility — my part-time staff fell under that declaration. My live-in worker stepped up to the plate and got me through this pandemic. She hasn’t had a break and is looking forward to some well-deserved rest. Both of us were very concerned about infection spread from part-time workers who served a multitude of clients during their full-time duties.

Like Araña, Coughlin is only now beginning to relax a little. At the time of writing this (first week in June), he was just considering the idea of bringing back one part-time worker, primarily so he could give his primary caregiver some much-needed respite. Marks, who is also a CSIL client and, as a C-5 quadriplegic, relies on the same approximate amount of care as Coughlin, also reports experiencing high levels of stress and the need for creative problem-solving to make it through the worst of the pandemic.

“I had been watching the news and seeing China welding doors shut for entire apartment complexes, and Italy, Spain and France getting hit, and the USA denying it would be an issue,” says Marks. “There were definitely some times I was concerned. I slept with a thermometer and pulse oximeter beside my bed, and still do. On a scale of one to ten, I felt like (my stress) went from a three up to a seven or eight as far as increased risk.”

At the start of the restrictions, Marks had two roommates.

“One left about March 12th to isolate with their family, and the other one isolated with me as a caregiver back in the beginning, but that only lasted about ten or 12 days before they also went to go isolate with family,” he says. “Luckily, two of my longer-term caregivers came back to help, and another friend helped out with some shifts—which paradoxically was great but also increased my risk of exposure to COVID-19. I needed all three to fill in the shifts for the week, but by any math that multiplied my risk of exposure coming into my house many times.”

All three were never in doubt of the threat, and did their best to minimize the risk.

“For the first month or six weeks, caregivers would come in and remove their shoes, wash their hands really well, and put on a mask,” says Marks. “We would both wear masks for the shift except for eating, brushing teeth, and showering, where I would remove mine briefly.” He adds that he started to relax the protocols gradually beginning in mid-May, when it started to become clear that BC—and Vancouver Island in particular—had managed to avoid much of the community spread that had become so disastrous in other provinces. Coughlin and Araña also began to breathe a little easier and relax their protocols around the same time, although both are still instructing their staff to practice superb hygiene and use personal protective equipment, or PPE.

“I’ll insist that the part-time staff mask and glove up, at least until we get a vaccine,” says Coughlin.

“All my home support workers continue to wash their hands as soon as they arrive and use PPE at all times,” adds Araña.

TAKING THE INITIATIVE AND BEING PREPARED

Disturbingly, the trio have been left with the impression that they’ve been dealing with the crisis largely on their own, with little or no support from their local regional health authority or any other government body.

“I was extremely frustrated and disappointed with VCH,” says Araña. “They never communicated with us, their patients, about what they were going to do to protect workers and patients. They never contacted or sent us any communication about any new policies or procedures that they were going to create and implement during these difficult times dealing with the COVID pandemic. I feel strongly that they needed to do more to protect the home support workers in order to protect and keep us, the patients, safe and healthy.”

In Coughlin’s case, his concern was about not being recognized as being a priority when it came to getting the supplies he needed.

“I had very little supply of PPE when the public health emergency was declared,” he says. “The usual sources for this supply dried up completely. I tried to get some from the health authority. They told me their supply was for the front-line workers. I contacted Safe Care BC and they were able to secure a donation of about two months’ supply of PPE for me.”

While all three are happy to be through what appears to be the worst part of the pandemic, none are relaxing this summer. Instead, all three are putting their faith in the best scientific and expert advice—all of which suggests that a second wave is possible, and that it may be even more catastrophic in the absence of a viable vaccine or therapeutic treatment.

“I’ll be trying to secure more PPE, if and when it’s available,” says Coughlin. “I’ll also be looking to hire more part-time staff.”

Marks is going a few steps further.

“I have masks and hand sanitizer ready, and other PPE too. I also built a greenhouse and planted a garden, and a friend is helping me build a chicken coop and I’m getting some chickens. So that’s my plan for the next six months. The chicken coop, greenhouse and garden I’ve been thinking about for years, but finally started making it happen at the end of March. On the island, we only have three days to a week of food and supplies in case of a natural disaster, and we just had a reminder of that during the early days of the pandemic. I think growing a few veggies and having some chickens, and supporting local businesses and food production is smart and necessary. I have no idea what I’m doing but I’m doing it anyway.”

THINGS TO THINK ABOUT…

Despite their preparations, all three aren’t exactly confident as they contemplate the possibility of a second wave. However, they all have some advice to offer other Peers in the same boat.

“I have a great relationship with all my home support workers, so I’m able to communicate how imperative it is to follow the instructions from (BC Provincial Health Officer) Dr. Bonnie Henry about ways to protect ourselves during the pandemic,” says Araña. “Advocate for yourself. Don’t be afraid to express your concerns. Be assertive. We must do everything we can in order to keep safe and healthy.”

“Plant a garden if you can; stock up on PPE for the fall,” says Marks. “Now is the time to press for a universal basic income that adds to disability supports and does not penalize us.”

Marks also suggests keeping an open mind and taking the initiative to look beyond our borders where other countries have had success with different approaches.

“The Japanese guidelines are to pay attention to closed spaces, crowded spaces, and close contact,” he says. “Minimize those times, ventilate and provide airflow through indoor spaces where possible, and wear masks when you can’t maintain distance if you have to go out in public.”

Marks also has some words of wisdom about how you treat your caregivers. “Remember, don’t make it too stressful or your caregivers because it’s already stressful enough. Look for ways you can appreciate them; I was fortunate to be able to get three of mine health and dental coverage for a year along with a small raise.”

The last word goes to Coughlin.

“Be prepared, be prepared, be prepared,” he says. “I never planned for this kind of disaster. I’m prepared for an earthquake or another kind of disaster, and the officials say that we should be able to survive on our own for 72 hours. Three months is pushing that somewhat. When I worked with the BC Office for Disability Issues, our staff developed a Disability Lens—a guide for policy developers. Clearly it was not used in the response to this global pandemic. My hope is that, in future disaster planning, folks like me will be considered. It sure didn’t happen this time. I was on my own.”

SCI BC will be working over the summer months to improve the support for all of our Peers, particularly those who rely on caregivers, in the event of a second wave of COVID-19. We’re making our concerns and recommendations known through a number of channels, including the BC government’s COVID-19 Disability Working Group, of which our Executive Director, Dr. Chris McBride, is a co-chair.

This full article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of The Spin. Read the full version alongside other stories, including:

- Born to Ride

- Brace Yourself

- Grasping the Subject

- and more!

Read the full Summer 2020 Issue of The Spin online!